Wars do not end in peace negotiations but at the ballot box, argues the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) in the introduction to its latest Ukraine war sentiment survey.

The conclusion of the US war in Vietnam, the French war in Algeria, and the wars in the former Yugoslavia were all preceded by a weakening of public support either as the result of elections or even as reflected in opinion polls.

Will the same apply to the Ukraine war?

Newly published survey data suggests Europeans remain united in their support for Ukraine, more united even than a year ago. Ukraine has – with exceptions – brought together normally opposing wings of the political spectrum. The backing of the all-powerful US, and its military, has been a key factor in this cohesiveness, respondents suggested, as has Ukraine’s surprising ability to push back Russian forces over the course of the 13-month conflict.

This has had knock-on positive effects for the European Union, which appears stronger today than a year ago. The right-wingers who have taken power in countries such as Italy have toned down their Euro-scepticism.

There are however dark clouds on the horizon, as the survey’s authors point out. What would happen if a Republican candidate becomes US President next year?

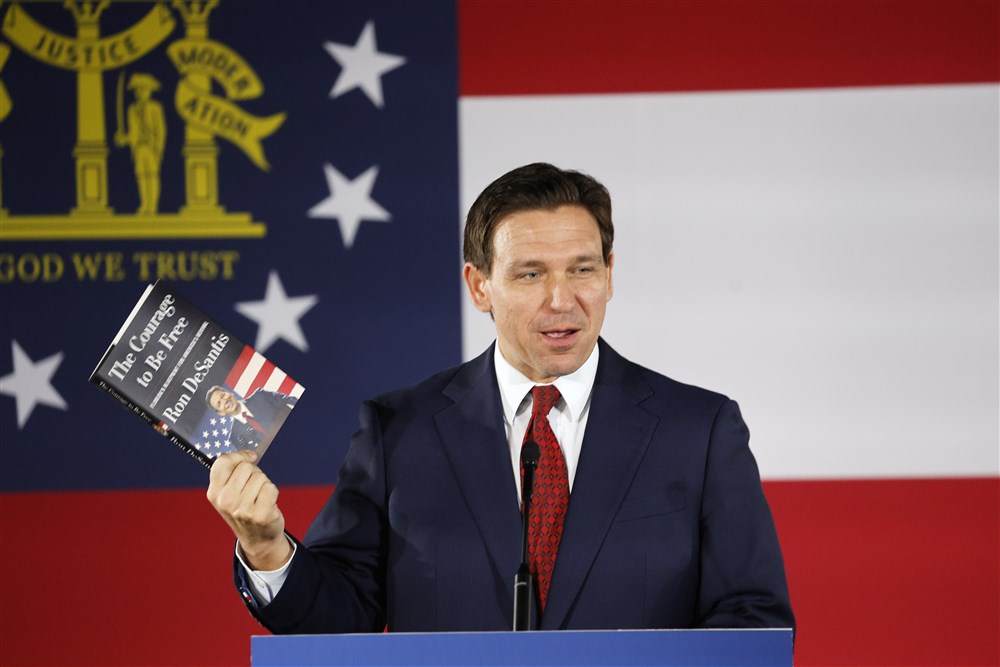

Florida governor Ron DeSantis, widely expected to try his chances, has made the news this week with comments suggesting Ukraine and its war do not count among the United States’ “vital national interests” and that the conflict is in essence a “territorial dispute”. Donald Trump, always mercurial, could shatter bipartisan support for the war by just winning the Republican nomination, it has been claimed.

A withdrawal of US support would change the European chessboard dramatically, and European nations, the ECFR suggests, should use the next year to plan for all possible outcomes.

To some extent this is happening. Poland, for example, is building up what some say could become the European continent’s biggest army.

EU nations are however notoriously poor when it comes to military cooperation, or even cooperation among intelligence services. They will – even today – not reveal details of their ammunition stocks to each other (as reported by the Brussels Signal on March 10). There has been endless talk about the creation of a ‘European army’ over the last three decades, and little progress on even the most basic building blocks of such a force, including joint procurement.

Faced with an emergency drive to provide Ukraine with 155mm shells, EU states, by way of example, are arguing about where these shells should be bought: in Europe only, or from non-EU countries too?

Public sentiment is notoriously fickle and support could fade if Ukraine’s successes go into reverse, the ECFR concedes. Europeans are increasingly concerned with the economy and purchasing power in particular. Support for Ukraine could vanish if Europe slides into recession, or worse.

The ECFR survey was conducted in ten countries. These did not include Hungary or Bulgaria, where attitudes towards Russia are more favourable. The survey shows Italy is the “weak link” in the pro-Ukraine alliance, according to local newspaper La Repubblica.

For details on who funds ECFR, see this web page.