The EU has moved closer to an agreement on a hotly contested nature restoration law, though it has been heavily watered down from earlier proposals.

The Council presidency and European Parliament representatives reached a provisional political agreement on the new law Thursday night.

Over 80 per cent of European natural habitats are now in a poor shape, says the EU. Past efforts to protect and preserve nature have not been able to reverse this deterioration.

The new law aims to restore at least 20 per cent of the EU’s land and sea regions by 2030, and all ecosystems in need of restoration by 2050.

It establishes explicit, legally binding requirements for nature restoration in those habitats, which include agricultural land, forests and marine, freshwater, and even urban areas.

Member states will need to submit regular national restoration plans to the Commission, showing how they will deliver on the targets, and then monitor and report on their progress.

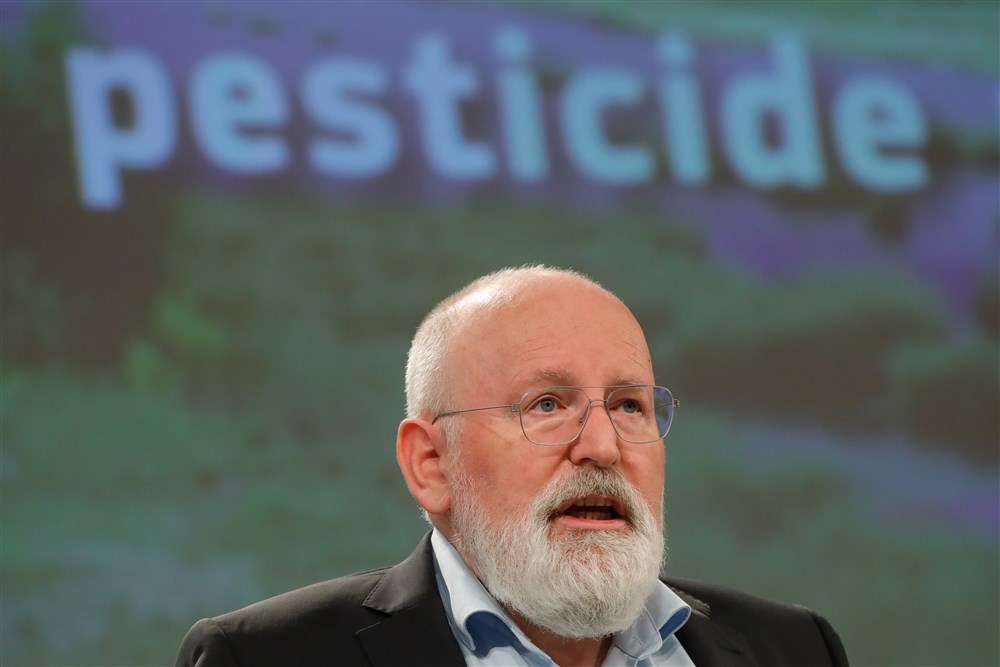

This current agreement is a far cry from the ambitious legislation put forward by the then-climate commissioner, Frans Timmermans, who afterwards stepped down to return to Dutch politics.

Opponents argued the original proposals would harm EU food production capabilities at a dangerous time, and that the proposals exceeded Brussels’ powers to implement.

Pressure from farmers and industry made the Commission strongly water down its ambitions, as the European Parliament and some Member States threatened to oppose it.

In response, the initial target area became limited to areas already protected under the Natura-2000 goals, until 2030.

Instead of requiring states to stop the deterioration of nature, they are now only obliged to make an effort.

The Commission has introduced an emergency brake, permitting members to set aside nature goals when food security is threatened.

And while the initial plan called for improving biodiversity on ten per cent of agricultural land, the current proposals do not establish a precise percentage.

The many dilutions make took place after even Timmermans’s own country voted against the original version of the law in the Europan Council.

In the European Parliament, resistance was even fiercer, led by the majority European People’s Party.

The European Parliament and the 27 Member States must now give their final vote on the current draft legislation, which is expected to be a formality.

The law’s original opponents may be more satisfied with the end result than its initial supporters.