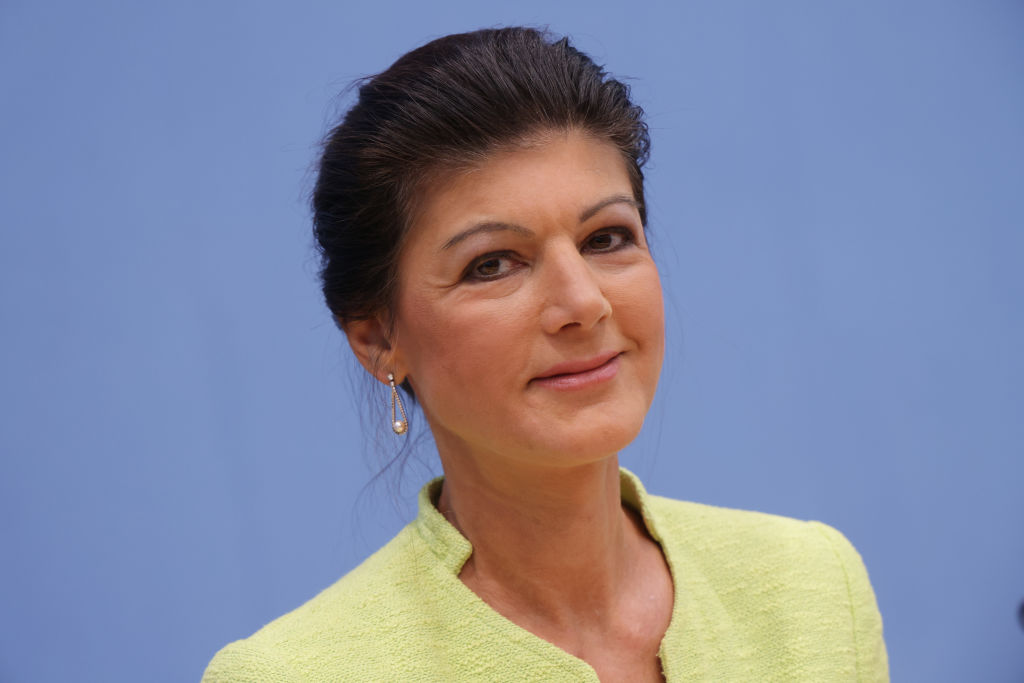

Banning the hard-right German AfD party is wrong and Viktor Orbán’s policies are sensible, says Sahra Wagenknecht, the country’s maverick hard-left star.

Wagenknecht left The Left (Die Linke) party to form a migration-sceptic left-wing party with nine other MPs on 23 October. Polls now suggest her new party could win up to 20 per cent of the national vote.

The Alliance for Germany (AfD) currently polls second with 21 per cent, behind only the governing Christian Democrats with 30 per cent.

There are increasing calls to ban the AfD, with president Frank-Walter Steinmeier saying Germany’s “constitution cannot encompass those who are enemies of the constitution”.

Wagenknecht disagrees. “I think the demand for a ban on the AfD is completely wrong, and I think the discussion about it is dangerous”, says the MP, now leader of the eponymous Bündnis (Alliance) Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW).

Banning unpopular parties “simply because they become too strong is incompatible with a free society”, she says.

Likewise, fighting a political competitor “with unconstitutional motions for a ban is incompatible with a democratic claim”, she adds.

Wagenknecht wants to convince AfD voters to give her their vote, because she disagrees with the party on economic and social policy.

These ideas “would make our country even more unjust”, she says.

The AfD has played a useful role in bringing the migration crisis to the political fore, she argues.

Every asylum seeker costs the taxpayer €20,000 euros per year, “something that is hard to explain to pensioners who worked their entire lives”, she says.

Her former party, the hard-left Die Linke, is not her political opponent, and she hopes the party will “find itself again”, Wagenknecht says.

The party’s leadership is following a vision voters find unappealing, and causing the party’s downfall, she claims.

Choosing “open-border activist and a radical climate activist” Carola Rackete as a top candidate for the European election is an example, she says.

By contrast, she has kinder words for Hungary’s PM Viktor Orbán. “I don’t have to like Orbán to say that what he is doing is sensible in the interest of his country,” she says.

Hungary has imposed stricter migration policies and continues to import substantial amounts of Russian gas and oil, causing prices to remain low.

Regarding her own future, Wagenknecht says she does not want to be her new party’s president and hinted that Amira Mohamed Ali, Die Linke’s former leader in Parliament, might want to take the role.

She may be open to being its top candidate in the upcoming European elections, but her main focus will remain on the federal German level, she says.

Her party’s platform calls for a ban on immigration and relaxing sanctions against Russia.

It also advocates raising the minimum wage to €14 an hour, increasing tax deductions, and significantly boosted taxes on higher incomes and assets.