As many as a million Russians fled abroad in the first year of the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine. Now thousands are returning home, delivering a propaganda victory to President Vladimir Putin and a boost to his war economy.

With the war still raging, and the man who started it about to assume another six-year term in power, many Russians are confronting a difficult choice. Facing rejections when renewing residence permits, difficulties with transferring work and money abroad, and limited destinations that still welcome them, they’re opting to end their self-exile.

“The business didn’t work out, no one is really waiting for us” abroad, said Alexey, a 50-year-old former political consultant from Moscow, who moved to Georgia to work as an entrepreneur after being detained at an anti-war rally in the Russian capital. He returned when his business’s finances ran out, Alexey said. He and others interviewed by Bloomberg asked not to disclose their last names for security reasons.

The February 2022 invasion provoked a mass exodus from Russia on a scale not seen since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Many left to register dissent against the war, and also out of fear of mobilisation. When Putin ordered a call-up of 300,000 reservists in September 2022, it triggered a new wave of departures by hundreds of thousands of people.

The outflow has slowed, if not reversed. In June, the Kremlin boasted that half of all who fled in those early days had already returned, and that seems to reflect available statistics from the most popular destination countries as well as data from relocation companies. Based on client data at one relocation firm, Finion in Moscow, an estimated 40 per cent to 45 per cent of those who left in 2022 have returned to Russia, said the company’s head, Vyacheslav Kartamyshev.

Putin praised the return of business people, entrepreneurs and highly qualified specialists as a “good trend.” He holds up the influx as a sign of support for his policies, regardless of the actual reasons for their homecoming, and evidence Russians have “a sense of belonging, an understanding of what is happening.”

The comeback stories are actively used in propaganda as a confirmation of “Russophobia” in the West, said Tatiana Stanovaya, founder of the political consultancy R.Politik and a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. For Putin, this matters, because “it fuels him, gives him additional evidence that he was right,” she said.

Thousands of returning expatriates are also helping Russia weather wartime sanctions and deliver a solid economic performance. According to Bloomberg Economics estimates, reverse migration has likely added between one-fifth and one-third to Russia’s 3.6 per cent annual economic growth in 2023.

Still, returning workers only constitute an estimated 0.3 per cent to the total number of employed. That does little to ease the acute shortage on the labour market, but underscores repatriates’ outsized contribution to economic activity.

For some, Russia now offers better opportunities and working conditions than before the war because the country is trying to attract back scarce specialists. IT programmer Evgeniy and his family returned after about a year of living in Almaty, Kazakhstan, when he received an offer to work in Russia with a salary and under conditions that he “could not even dream of before.”

“This is a gift for us,” said the president of the Kurchatov Institute National Research Center, Mikhail Kovalchuk, after CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, known for the Large Hadron Collider project, announced that it would stop working with Russia’s specialists this year. That means the return of scientists to Russia, he said.

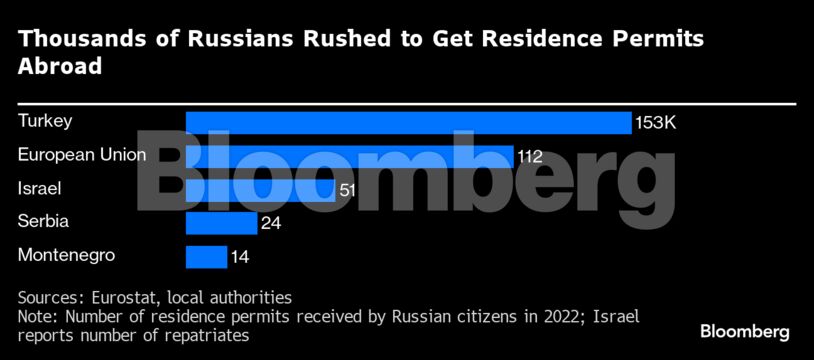

While estimates of the number who left vary greatly, Alfa Bank economists in Moscow estimated that Russia lost about 1.5 per cent of its entire workforce in 2022, or roughly 1.1 million people. While some went to Europe, many went to places such as the United Arab Emirates, Thailand and Indonesia, states that didn’t follow the US and its allies in sanctioning Russia, as well as to neighbouring former Soviet countries.

Russian citizens have faced difficulty or refusal when trying to renew expiring residence permits, according to Finion’s Kartamyshev. Most of those who do wind up choosing to return to Russia, he said.

Finion’s data shows that even in mostly friendly countries, such as Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, Russians have come under greater scrutiny. Several European countries, particularly in the east, have made it much harder for Russians to receive or renew temporary residence permits, as has Turkey, surprising tens of thousands of Russians, who then faced a choice of returning home or looking for another country, Kartamyshev said.

The current number of short-term residence permits for Russians in Turkey stands at around 60,000, halved from 132,000 in 2022, official data shows.

Data from Georgia’s national statistics office show the number of Russians who left the country increased by six times to 35,344 in 2023, while arriving migrants declined 16 per cent from a year ago. Kazakhstan reported 146,000 newcomers from Russia by the end of 2022, but a Russian diplomat to Almaty claimed that after a year no more than 80,000 stayed.

The repatriation process is likely to continue. According to a study by political scientists led by Emil Kamalov and Ivetta Sergeeva at the European University Institute in Florence, only 41 per cent of Russian migrants, and in some countries just 16 per cent, consider their status stable or somewhat stable in their host societies. That insecurity is further exacerbated by 25 per cent reporting experiences of discrimination, either from local people or institutions.

They found that “the world literally rallied against them,” said Anna Kuleshova, a sociologist at the Social Foresight Group, who interviews Russian immigrants. “They came back with a feeling of resentment and the feeling that ‘Putin was not so wrong after all. They really hate us.’”

Once home, many repatriates who left over their opposition to the war find different challenges. Alexander, 35, a banking IT specialist, returned to Russia from Azerbaijan because his family wasn’t comfortable there. He found a job at a large Russian bank where he said most of his colleagues support Putin and believe the propaganda about the war.

He doesn’t argue his colleagues on the matter. “It’s not safe to convince colleagues,” he said. “I’m waiting for this nightmare to end.”

What Bloomberg Economics Says…

First, returning migrants tend to command higher wages and to be employed in high value-added industries — surveys show that income level was highly correlated with the likelihood of leaving the country to avoid mobilisation in 2022. Second, returning workers boost activity in domestic consumer-oriented industries, such as household services, retail and real estate, instead of spending their income abroad. The latter also meant softening the capital outflow from Russia over the course of 2023.

Alex Isakov, Russia economist