In 2023, Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer appeared before a raucous crowd in a beer tent, proudly chugging a beer in one go. It made for great pictures and got great press. But later, the person running the tent confessed that Nehammer’s drink had been almost entirely water, with only a little beer.

Such an anecdote is small, but it perfectly encapsulates all that has occurred over the last few weeks of Austrian politics – and the past decade of Western populism.

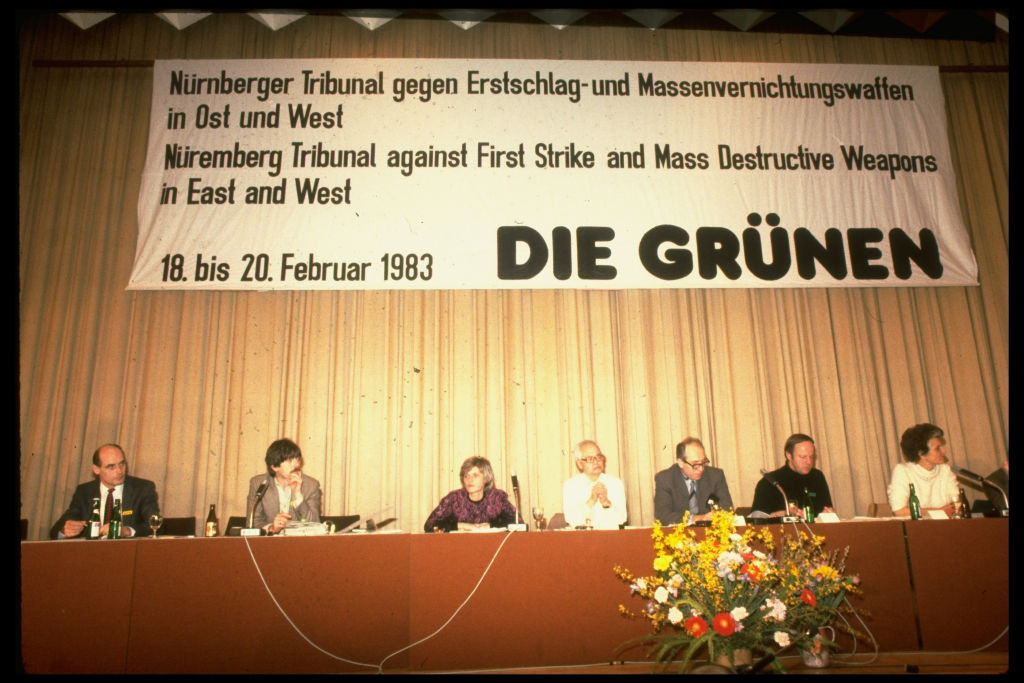

Starting with the most immediate news: the Austrian establishment’s attempt to put off the inevitable has collapsed. President Van der Bellen, the former Green party leader, has been forced to invite Freedom Party populist Herbert Kickl to form a new government. There are no alternatives. For the past three months, the “coalition of losers” – the centre-right People’s Party, the centre-left Socialists, and the neoliberal NEOS – tried to form an unworkable three-party government.

It was clear that, even had they formed one, it would not have lasted a full term. Germany’s own three-party experiment had just failed, and that one at least had two parties (the German Socialists and the German Greens) who were nominally on the same side. Plus, Austria’s budget issues are massive, and only the NEOS were attempting to solve them. When it became clear that the Socialists were unwilling to commit to any real spending cuts, the NEOS party leader pulled out.

At that stage, the People’s Party and the Socialists tried to re-form the so-called “grand coalition” of the two establishment parties. But there is nothing grand about such coalitions: as both parties are fundamentally opposed to one another, they often only tinker around the edges. Plus, such a “grand” coalition would have had a majority of exactly one seat, meaning that if anyone was ever out sick, the government would be unable to pass anything.

Yet they still tried. Why? The fault must be laid entirely with one man: the water-chugger, Chancellor Nehammer. The chancellor had promised not to work with Kickl during the campaign, calling him a threat to democracy (without ever saying exactly how he was a threat). After his party came in second in last year’s elections (to the first place Freedom Party), Nehammer sought to form the three-party coalition, he claimed, to save Austria from Kickl.

But conveniently, this also meant that he would remain chancellor. Nehammer had only become chancellor in 2021 when his predecessor, Sebastian Kurz, was forced out. Given the choice of being a three-year man or an eight-year man, Nehammer clearly was more interested in the latter, and sought to stay in power by working with the Socialists and the NEOS.

Doing so would have required compromise, as creating any government does. This is not inherently a problem; indeed, it is the essence of most democracies. But where a party decides to draw a red line is often telling.

For the Austrian centre-right, one would have assumed the line would be migration. Kurz, the former People’s Party chancellor, had made strides for his party in opposing the rampant illegal migration which has plagued the European Union over the past decade. This past year, the Freedom Party under Kickl had likewise come in first place on a platform of “re-immigration,” sending migrants back home. This is not unique to Austria. Voters around the West have made clear that mass migration needs to end. It was what propelled America’s President-elect Donald Trump to his massive victory this past November. In Trump’s own words, the border was “a bigger factor” than the economy. It propelled Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni to win in Italy, the French populist-right to win the most votes in their recent parliamentary elections, the populist-right to surge in Germany, and more.

Therefore, drawing a line in the sand over extremely strict migration rules and laws would have been an easy win for Nehammer. But it seems to have been a secondary concern. In fact, just over a week ago it was reported that all three parties had agreed on some basic migration prospects (and if all three agreed so simply, the rules could not have been so severe in reality).

So what was Nehammer’s red line? In his resignation statement, he made clear exactly what it was: wealth taxes. This had reportedly been a major sticking point in the negotiations. The Socialists had demanded new wealth taxes, and the centre-right People’s Party had flatly refused.

The People’s Party was not inherently wrong to do so. Wealth taxes punish success and just serve to double-tax individuals. Plus, Austria already has some of the highest tax rates in the European Union, and it seems that the Socialists simply wanted to punish the well-off with a symbolic win instead of actually reforming the government and fixing Austria’s budget issues.

But even so, it is extremely telling that the red line for the centre-right was taxes on the wealthy instead of what voters actually care about, migration. This too is not unique to Austria. Around the West, since the end of the Cold War, the centre-right has seemed somewhat content to fight for the rich without paying heed to border issues. Massive tax cuts have always been first and foremost, followed by lip service to border issues. The new populist-right, under leaders such as Trump and Kickl, have reversed this trend. Yes, they of course value tax cuts, but they have made borders the priority.

If one looks for a single reason for why the populist wave has been flowing so continuously over the remnants of the old Right, this is why. The populists are seeking to give their voters a sense of community, a sense that their nation is a real thing that can be defended. As America’s Vice President-elect JD Vance has said, “America is not just an idea. It is a group of people with a shared history and a common future. It is in short, a nation.” The same goes for Austria and all other states rife with populist anger.

For decades, the centre-right offered a lesser variant of Vance’s formulation. Voters were given a big gulp, only to find that instead of beer, it was mostly water. Now, they are sick of fakery – and they want the real thing.

Brexiteers voted ‘Out!’ but are left still tied to foreign regulators they did not elect