From the beginning of the Trump administration, Brussels-based officials have been struck by the new president’s complete lack of desire to deal with them. When they have finally met – such as when Vice President JD Vance met with Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and others – EU officials were so thrown off with the America First rhetoric that they could only wrap their heads around it by denying that Trump and Vance really meant what they said.

But part of the reason why the Trump administration – and, I suspect, other governments around the world – may be holding back on taking EU leadership seriously is because its hard to tell who is actually in charge of the bloc.

Now that her internal combatant, Charles Michel, is out of commission (pardon the pun), Ursula von der Leyen is clearly trying to make a play for being the “sole” leader of the European Union. But her background (a failed German defence minister) and a less-than-spectacular first term (her greatest achievements domestically was mandating the USB-C charger and the passage of the Green New Deal, much of which she is now trying to unwind) make it hard for her to claim the mantle of leadership. Plus, the nature of her position – “President of the European Commission” – is also hard for foreigners not steeped in EU parlance to grasp. Being in charge of an EU institution without being in charge of the EU itself makes her seem like a glorified clerk, not the leader.

Kaja Kallas, the current High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, is certainly seeking to be the voice of the European Union to allies and adversaries around the globe. But her position – note that she is not technically a foreign minister, as she cannot speak for all EU governments unless given approval – limits her ability to speak affirmatively. Plus, having been prime minister of small Estonia and leaving that office under a scandal-coloured hue does not really give her the credence to lead the bloc of nearly 450 million. If the European Union were federal, her home country would perhaps cause her less of an issue; after all, former American President Joe Biden hails from Delaware, one of the smallest states in the US. But given the fact that the European Union is not federal, hailing from a relatively small country – even one trying to pull its weight when it comes to things like defence spending – makes it hard to be taken seriously as leader of all.

Which turns us to how people have usually looked for leaders in Europe: on the national level. Normally, “Who leads Europe?” was a question which meant “Which European leader is dominating the rest militarily?” Since 1945, the continent has sought to work together instead – but that does not mean domination cannot come in other ways.

However, a survey of the current “great powers” in Europe reveals something startling: none of them can truly claim to be “leader” either.

The Germans would normally have a straightforward claim. Possessing far and away the largest population – with over 80 million, nearly 20 per cent of the EU’s entire population – and the largest economy, the country should on paper be a shoo-in. But twenty years of rule by Angela Merkel left it rudderless, with a rapidly de-industrialising economy and massive numbers of new migrants and refugees, many of whom have been committing a spate of deadly attacks in the name of jihad. This in turn has allowed for the rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), which just got its best result in any national election ever; the Christian Democrats (CDU), which promises stability for Europe, “won” with its second-worst result ever, and will now – due to a refusal to work with the AfD – be forced into an unhappy and unstable alliance with the toxically unpopular Socialist Party of Germany (SPD). Such “grand coalitions” rarely produce phenomenal policy, and certainly will not give Germany the inspiration to lead Europe.

Which normally would give an opening to their western neighbour, France. President Emmanuel Macron has clearly long-desired for France to become dominant on the continent once more, linguistically and militarily. He has frequently called for a European Union Army – but one has difficulty envisioning that he imagines that it will be commanded by a Bulgarian. Unfortunately for Macron, his moment to seize Germany’s weakness has likely passed. He is wracked with discontent at home; two prime ministers already fell last year, and his current one is constantly on the cusp; a new scandal – claims that the Prime Minister François Bayrou knew about and failed to stop sexual abuse at a school his children attended – could weaken the government further. Macron himself is radioactively unpopular, with an approval rating of only around 23 per cent. Any promises he seeks to make in order to bolster France’s power in Europe – from nuclear sharing to stationing troops in Ukraine – cannot be taken seriously by others, as he has effectively no further political capital and could in just two years be replaced by a member of the populist-right.

Poland is making a play for the largest military on the continent, and it has genuinely done an admirable job. But the country has two different supreme courts which seem to swap authority depending on which party is in power. Likewise, Poland’s population – just under 37 million – is rather small, and its geographic placement – between Russia, Russia (Kaliningrad), and Belarus – means that it will always have to spend most of its energy looking out for itself instead of minding the European shop.

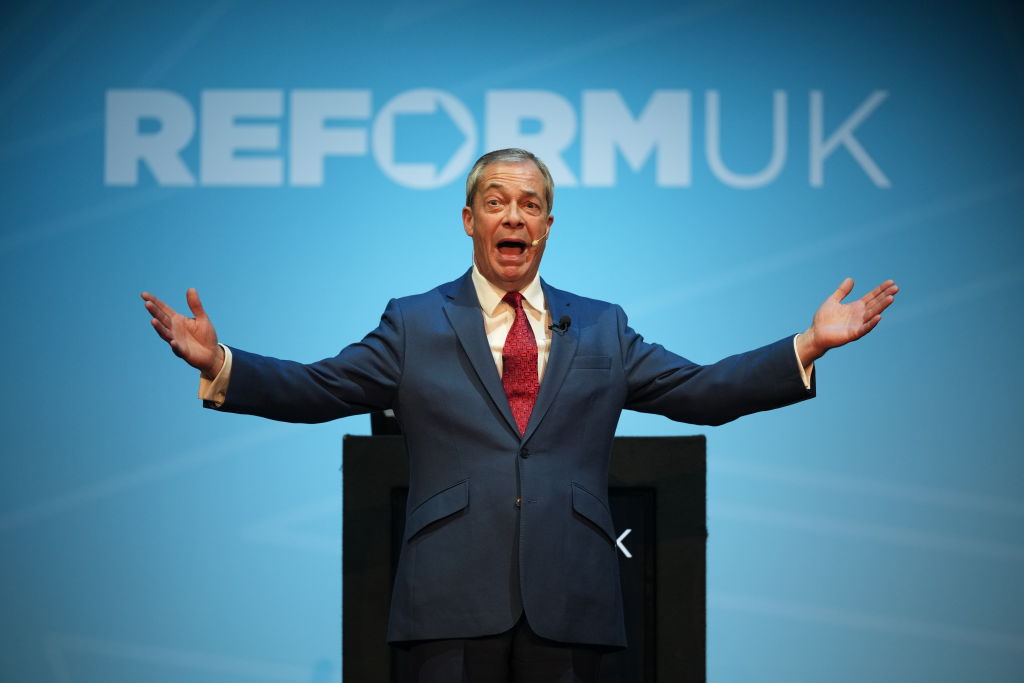

The United Kingdom? It’s not even a member of the European Union, and so could not feasibly seek to “lead” the continent. But even if this was not an issue, the government – less than a year old – is likewise incredibly unpopular, and is losing in the polls to Nigel Farage’s populists. And while it has nuclear weapons, it only has those so long as Scotland never leaves (as there are no other ports fit for their nuclear submarines) – and it is hard to take a continental leader seriously if it is nervously biting its nails off once a decade over a Scottish independence referendum result.

When the liberal internationalists in Brussels wonder why their ideology and their positions are no longer being taken seriously by their own people and by their allies, instead of launching into denial, they should draw up an org chart instead. Perhaps then they’ll realize that there’s no one truly in charge.

‘Rules based international order’ is dead, 20th century never coming back