Have you seen the trailer for the new Hollywood film, Warfare? I’ve been watching it for three days now, on repeat. It is the story of US Navy SEALs in Iraq caught in a 2006 blood-spattered ambush in Ramadi. (“Spattered”? Understatement.) The Times of London called it “a movie that’s as difficult to watch as it is to forget. It’s a sensory blitz, a percussive nightmare and a relentless assault on the soul.”

The Wall Street Journal said, “It’s one of the most intense re-creations of combat ever put on film.”

The trailer is all I have, because the film has not yet opened where I live. Still, I am left with the explosions, legs blown to pieces, grenades, fear and courage, there it is, war, all of it, even in two minutes and 24 seconds of trailer. Nothing fiction here. It is all built on the memories of the men who were there, told in 95 minutes of real time.

I admire every moment – moment? Wrong word. Moment sounds romantic. I stand riveted to every blast of it, every ferocious reply to the enemy– but the trailer is not enough. I have pulled up parts of the script online.

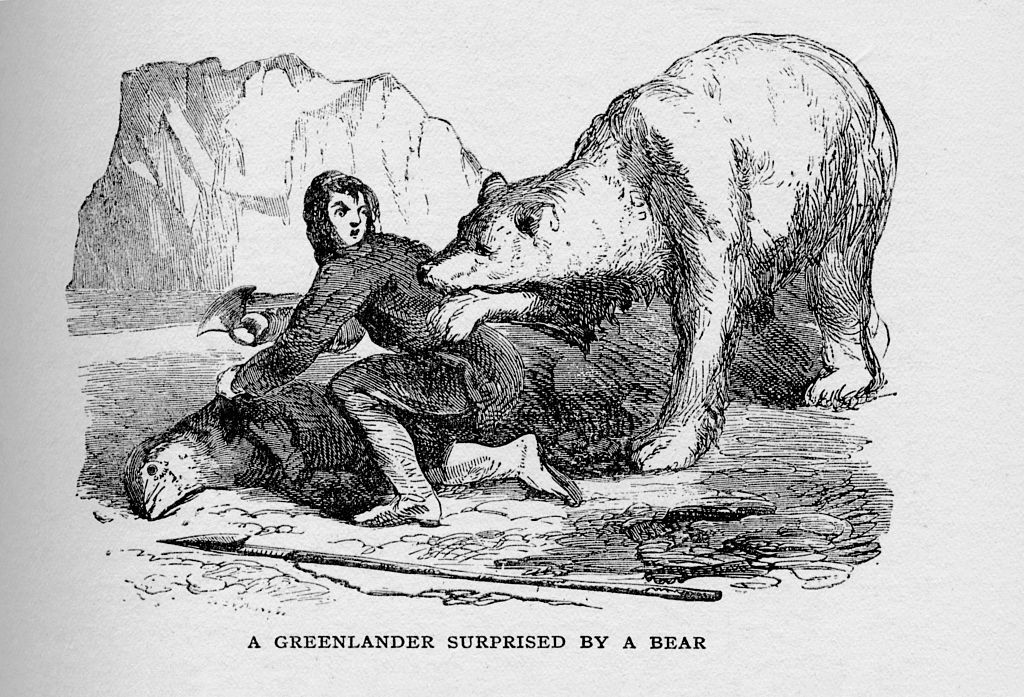

Watch, learn what these extraordinary creatures – these men, that is the point, only men, and that is why I watch them in fascination, they are as foreign to me as the strange intelligence of an octopus – can do. Listen to their emotionless radio communication as the enemy closes in on the house the SEALs use as base: ‘We have the enemy on our building and all surrounding buildings.’ A dry summary, that’s it.

There are the screams of Sam, the SEAL whose legs are blown apart by a grenade. When the unit are going for evacuation, the wounded SEAL will be dragged and shifted by the men. No man left behind. But a comrade only says, ‘You gotta get ready, man. This is gonna hurt.’ The SEAL’s screams will stay with you.

Elliott, the sniper, is reporting on what the enemy are doing as he peers through his sight. They are “peeking with serious intent to probe.” The SEALs know what is coming.

Consider them all, the SEALs, and all their military comrades, these creatures with the strong backs, the powerful arms, running strapped with 100lbs of kit, the sniper skills, the training, the brotherhood, the fear masked by courage.

May I now, and take a breath because this is also “gonna hurt”, ask you to consider the recent news film of six women climbing into Jeff Bezo’s Blue Origin space craft and going for an 11-minute flight. They are calling themselves “astronauts,” or as one of the women in her fashion designer-made space suit said, “We put the ass into astronauts.” Another of these “astronauts” was offended nobody much was impressed. She compared her 11-minute ride to the historic space flight taken by American astronaut Alan Shepard in 1961.

I have nothing to add to either of those comments.

The entire trip was an embarrassment. Worse, it was an embarrassment because the hype selling it was that it was an “all-female crew.” Except they weren’t crew anymore than me being on a Ryanair flight makes me crew. And at least I don’t get in a Ryanair flight, go “Oh!” when I see the moon and pull out a daisy as some sort of moment of reverence, and I don’t giggle and scream, as the Blue Origin passengers did (what are they, eight years old?).

Please compare the two events. The film Warfare is an account of extreme men, men built to as close as they can get to human perfection. Watch what they can do, and for those of us secretly worried about how our arse looks in our spacesuits, be grateful they can inflict deadly warfare. We need them, the strength, the skill, or what the new US Secretary of Defence calls “lethality.”

Consider one of the great warriors of the West, Admiral Lord Nelson. His rule for warfare was that his men must “annihilate” the enemy. His men were the most highly trained, best equipped navy in the Napoleonic war. At the Battle of Trafalgar, 450 British and Irish sailors were killed, with 4,000 French and Spanish dead. Lethality.

By the time he had won Trafalgar, Nelson had almost nothing left with which to be physically strong, with an eye gone, an arm gone, a blast across his skull from flying metal, and a spine severed by a French sniper. But he still had his fight left. Told the battle was won for the British, his last words were, “Thank God I have done my duty.”

He was a man. What creatures they are.

And of course we have been told for years that adding women to fighting forces is just the same as adding more men. No, it is not, and at least the new US administration sees that.

Women can be good with computer warfare, for example. A woman with an edge to kill the enemy can certainly handle a drone kit, yup, just hit that enemy s.o.b. The patron saint of such women is the French revolutionary heroine, Charlotte Corday, who in 1793 bought a kitchen knife with a five inch blade, tricked her way into the bathroom of the Jacobin leader Marat and drove the blade through his neck into his chest. What a girl. No man could have pulled that off.

But there are times, important times in war, when it has to be men acting together to win a fight.

And they do it so well. I look at a film of a squad of sweaty, well-armed SEALs, Marines, soldiers, any of them, fighting and I rather love them all, as I would love a wolf pack going in for a kill. They are everything I am not. The closest I’ve ever been to a fight was being told by a British army officer that a sniper was near our position in Londonderry. I did the decent thing and went to hide in a pub. I left the officer to deal with the sniper. (“Carry on, chaps. I’m in the Monaco bar if you need me.”)

As for those women in the Jeff Bezos capsule, get out of the stunt. Women can be so much better than that. Go home. I don’t know, learn needlework. Gardening is good. Educating children is important. Being a wife to a brave man is best of all.

Remember, as the great warriors, the Spartans, told us: the only way to get a Spartan warrior is from a Spartan mother. You are the source. Every fighting man in Warfare is some mother’s son. Wear the honour.

Defeated West is pretending victory in Ukraine, but outsourced the bleeding to Kyiv