A large share of US military aid for Ukraine is not only old but in some cases dangerous for soldiers to use, a conference heard last week.

The so-called “failure risk” of the equipment was multiple times higher than that permissible for NATO armies, according to a speaker at a CEPS event in Brussels on July 4.

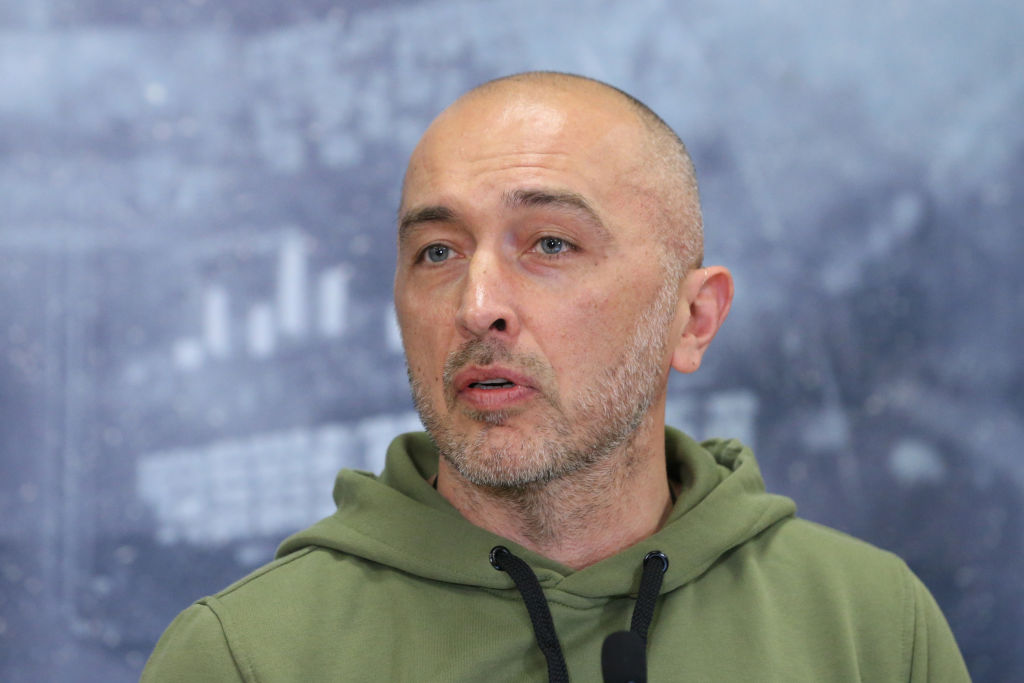

“A part of it was useful,” said James Hodson, an economist at the US Berkeley university, “but some had up to eight times the failure risk NATO standards would allow.” That level of unreliability, he explained, poses serious risks for Ukrainian troops using the systems in combat: weapons can jam, targeting systems may fail, or armoured vehicles might break down under pressure.

“Of course it is a risk for the soldier operating it,” said Hodson.

Hodson presented findings based on a six-month research project conducted with UC Berkeley and economist Daniel Gros, director of the Institute for European Policymaking at Bocconi University.

“We discovered that the US declared sometimes several times the same money or things given,” said Gros. “The vast majority of the equipment they gave was worth zero euro by US Department of Defense depreciation standards.”

According to Hodson, this means the equipment sent was often no longer usable by the US military. “They were in the end saving money by recycling.”

“What we see is that the EU has given a lot more—and newer—equipment,” he said. “This war is highly technological. A lot of what has been sent [by the US] is not useful for Ukraine in this situation.”

The report follows another by the Kiel Institute, an influent German research centre that has tracked all announced and delivered assistance to Ukraine, confirming a broader shift: Europe has now overtaken the United States in total money pledged to Ukraine.

Gros noted that while early support consisted largely of grants, more recent assistance includes a growing share of loans. “There were much more total transfers at the beginning, and it decreases year over year, while the part of loans is increasing,” he said. Ukraine’s current balance of payments is “covered,” Gros added, but only “at a level that is barely survival.”

Based on the Kiel Tracker’s June update, Europe has moved ahead of the US in recent months. In March–April 2025, EU states and institutions allocated €10.4 bn in military aid—the largest two‑month total on record—and €9.8 bn in financial/humanitarian support. That surge helped push Europe past the US in military commitments (€72 bn vs €65 bn), a gap not seen since donations began. The increase was led by the Nordics (€5.8 bn), the UK (€4.5 bn) and France (€2.2 bn), while Germany’s contribution dropped about 70% to just €650m.

The comparison between the US and EU approaches has gained renewed attention as US domestic debates intensify. In March, the BBC challenged a series of claims made by President Donald Trump suggesting the US had provided $300 to $350 billion in aid to Ukraine—figures that far exceed publicly available data.

According to previous Kiel data quoted by the BBC, the US had spent $119.7 billion in the period analysed—well below Trump’s figure. Even broader US government estimates, such as the $182.8 billion appropriated under Operation Atlantic Resolve (which includes spending not directly targeted at Ukraine), fall short of the number cited by the president, the broadcaster claimed.

Trump has argued that US aid consists mostly of grants, while Europe is giving loans it expects to be repaid. The Kiel data shows a more nuanced picture: About 35% of EU aid has been in the form of loans—many of which are conditional or are expected to be repaid using revenues from frozen Russian assets. The rest has been provided through direct transfers, including military support and grants.