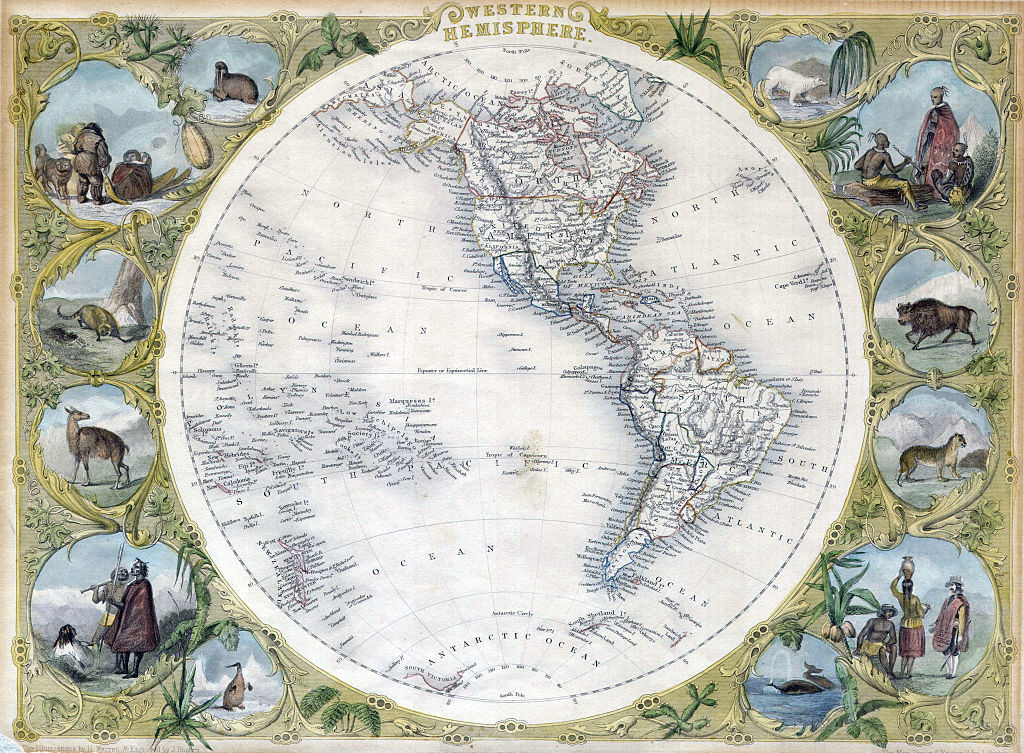

The scenario that Brussels Signal warned about half a year ago in this very column seems to be coming to pass, with Pentagon leaks suggesting that an epochal shift in American global posture is upon us. The rumour is that the upcoming US National Defence Strategy, due shortly, will prioritise the US “homeland” and the western hemisphere (the Americas) over countering China, let alone Russia.

Such a decision would be so momentous in its implications and so shocking in its advent – going, as it would, squarely against the core Indo-Pacific focus of US strategy over the past decade – that the US and Western foreign policy community still exudes an overwhelming sense of incredulity at the prospect.

Bewilderment is amplified by a perception of intellectual betrayal. The main author of the document, Undersecretary of War for Policy Elbridge Colby, made his name as a China hawk specifically advocating a stronger, not weaker, US military posture in the Pacific. His widely-read 2021 book, The Strategy of Denial, is wholly concerned with denying China regional hegemony as a matter of the highest priority in US defence strategy. Admittedly, the book came out before China’s giant manufacturing capacity got firmly coupled to Russia’s vast raw materials after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the West’s response. Still, how could he now work towards a policy that is almost the complete reversal of what he always stood for?

As the rumoured strategy is not out yet, many still hope that there may yet be time for course-correction. And it is also not beyond imagining, given some of the unorthodox ways of handling political issues that this Administration has so far evinced, that this entire affair is part of US diplomatic signalling in Trump’s negotiations with China, rather than an actual strategic pivot.

For some reason, international opinion has not yet fully realised that the main priority for this second Trump Administration is trade policy – and specifically the settlement of US-China trade relations – rather than security or even foreign policy as a whole. Unlike most, or all, previous White House regimes, in the Trump 2.0 era it is the principals holding the top economic briefs who are they key players in the president’s entourage and who are shaping the direction of US global strategy the most.

The influence of Scott Bessent (the Treasury Secretary), Jamieson Greer (Trade Representative) and Kevin Hassett (who heads the National Economic Council) arguably outweighs that of Marco Rubio (at State) or Pete Hegseth (War Department) because Donald Trump himself looks at the world and America’s role in it through a trade lens now more than ever before.

This is novel and worrying for allies accustomed to the idea of US military power as the fundamental ordering factor in the international system. American primacy in world affairs, on which Western security and prosperity has been based since the Second World War, has been underwritten by the Pentagon’s vast war-fighting resources and America’s edge in high-end military technology. But historically all this has, in turn, depended on the health and capacity of the US economy. In other words, security has always been downstream from economics.

And America’s economic position continues to decline in relative terms, especially with respect to China. In 2005 the US nominal share of global GDP was over 27 per cent, with the EU at 30 per cent and China at 5 per cent; in purchasing power parity values, the ranking was 20, 14 and around 10 per cent. Today, the nominal GDP share figures are around 24 per cent for US, almost 18 for China and around 16 for Europe; while in PPP figures China has already overtaken the US with almost 19 per cent to America’s 15.5 per cent, and the EU sinking under 15 per cent. On top of this, the US is running a $37 trillion debt, a vast $2 trillion annual deficit and its annual debt interest payments are over $1 trillion, i.e. more than the entire American defence budget.

Until recently, China’s rise has been primarily an economic event. We are now at a point where it has transformed into a technological and military event as well. It is becoming apparent that fully “containing” the Chinese phenomenon requires a military and economic effort on a scale that the US may not be able to afford any longer – or at least not without risking the entire economic future of the United States. Nor can more allied burden-sharing make a decisive difference.

So, a major change of tack is required: Some form of retrenchment, to give America room to breathe and get its own economy and “house” in order. Executed properly, this should be seen as a positive step; it is persistence in an obsolete strategic mode of thinking that represents the higher risk. The strategic competition with China will be unfolding over a very long term, and we should expect ups and downs; there is no sudden geopolitical obituary to be written for either side, even when major withdrawals or compromises occur.

Besides, nuances are vital here. It is a matter of emphasis. No one should expect a full US evacuation from the global security system; that is neither practical nor required. America will remain one of the two military-economic superpowers for the foreseeable future in almost any scenario, and at present it can still largely negotiate with China from a position of strength. But when the question of hard choices arises over how much of the global security burden to carry forward and at what economic cost, economic considerations will now have to prevail over military-strategic ones.

Pursuing strategic retrenchment – which is what a focus on the homeland would be – with an economic upside in view is made easier by the basic fact of American security: That the US is, at the end of the day, protected from invasion by two great oceans and that its involvement abroad has always been, fundamentally, a matter of choice not a matter of implacable necessity.

In this context, the idea of reprioritising US defence strategy away from the Pacific looks less like a foolish, shocking mistake and more as an attempt at a prudent, realist response in the face of a changing global balance of power. If world order can no longer be sustained by clear-cut US military advantage, and if trade and economic relations are so central to recasting the premises of global stability, it should not be surprising to see the erstwhile systemic hegemon adapting, seeking to reduce tensions and leaning more on non-military ways of shaping great power relations. The requirements of the new multipolar age seem to be making hard realists out of many strategists – including Bridge Colby.

Congress and the ‘Trump supremacy’