The European Commission is using the Jean Monnet Programme to promote a pro-European Union narrative across European universities and around the world, according to a new report by Italian journalist Thomas Fazi published on September 11.

In the report, from the Hungarian think-tank MCC Brussels, Fazi describes the initiative “which channels around €25 million per year to universities and research institutes in more than 70 countries” as “institutional propaganda”.

The programme was launched in 1990 to encourage teaching, research and reflection in the field of European integration studies in higher education institutions. It is named after Jean Monnet, regarded by many as a chief architect of European Unity.

According to Fazi, rather than focusing solely on neutral education about European institutions, many projects actively seek to cultivate a European identity, counter Euro-scepticism and promote the principle of supranational integration.

As part of Erasmus+ student programme, the EC describes the programme as a “public diplomacy tool” designed to enhance the visibility of European values, strengthen teaching and research on EU topics, and promote co-operation with non-EU countries.

The EC highlights its role in encouraging critical thinking, supporting teacher training and fostering dialogue on European issues.

The report argues that the initiative, far from being a neutral educational programme, is an EU-funded vehicle for ideological influence.

According to an official evaluation of the programme, Jean Monnet activities received €44.4 million in 2016 alone.

Fazi argues that these initiatives blur the line between education and advocacy.

In his view, Jean Monnet projects embed pro-EU narratives across disciplines such as law, history, politics, and economics, while marginalising critical or alternative viewpoints.

The objective is “to embed pro-EU narratives in the classroom”.

“Alternative or critical viewpoints, meanwhile, are marginalised,” Fazi said.

He warns that risks compromising academic independence, with universities functioning as instruments of political messaging rather than spaces for open inquiry.

“In many cases,” Fazi notes, “these projects aren’t even about specific policies. Their goal is to champion the EU itself and the principle of post-national integration.”

They are explicitly aligned with the EC’s vision of deeper European unity.

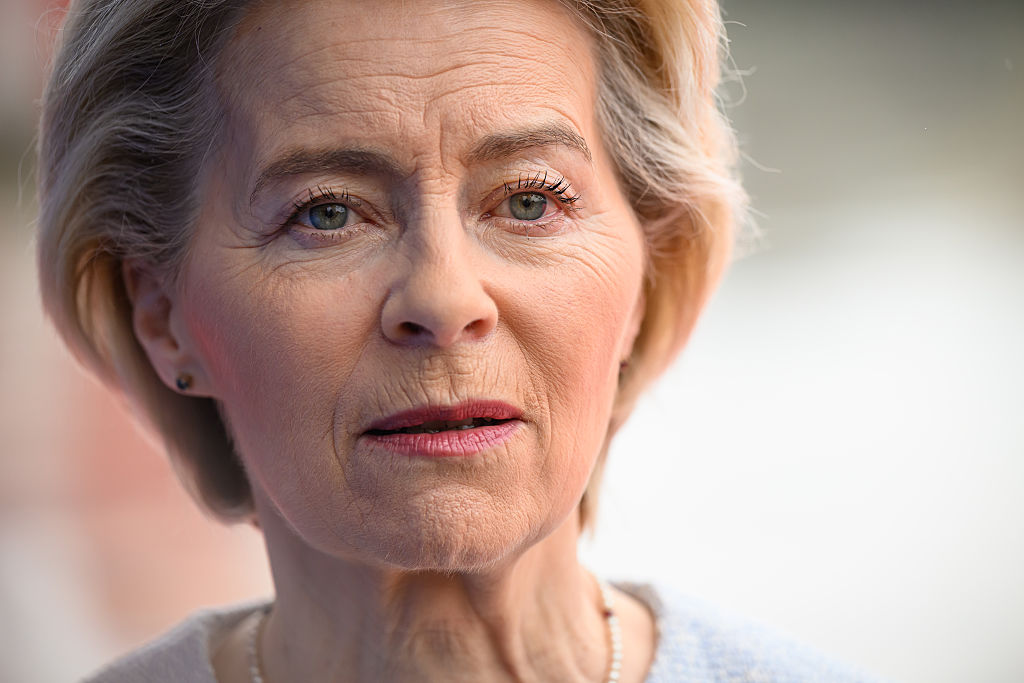

Meanwhile, in her State of the Union address on September 10, EC President Ursula von der Leyen announced plans to pour funds into media across Europe.

Critics warn that initiatives like the Media Resilience Programme, which is billed as supporting independent journalism and media literacy, could further entrench pro-EU messaging across the continent.

The EC is also rolling out “critical thinking and politics” courses aimed at secondary school students — whom it calls “first-time voters”.

According to the EC, these initiatives are designed to promote media literacy and help students navigate disinformation.

The focus on younger students reflects an emphasis on “fostering critical thinking skills early in the educational process”, it said.

In 2024, von der Leyen described disinformation as a “virus” to be pre-emptively countered, advocating “pre-bunking”.

Critics argued that the target audience suggests a more strategic dimension: shaping young citizens’ perceptions well before they cast their ballots.

The European Commission is pushing for media literacy across the bloc via courses in “critical thinking and politics” aimed at secondary school students, or what it termed “first-time voters”. https://t.co/TicY3dVqo7

— Brussels Signal (@brusselssignal) February 27, 2025