When I interviewed Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in July, I asked him, among other things, what his plan was to stop what he considered to be bad EU projects, including the budget. He replied without hesitation: “We have elections in April next year, President Kaczyński and Prime Minister Morawiecki will return to power, Andrej Babiš will win in October in the Czech Republic, and Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico is strong enough and will remain. Then the four of us, as the Visegrad Group, will be able to stop the crazy ideas contained in this project.”

So far, everything is going according to plan.

Babiš won and is now negotiating with his coalition partners to build a 108-seat majority in the 200-seat lower chamber in the Czech parliament. The European media has predicted the downfall of Slovak Prime Minister Fico several times, but none of these predictions has come true. In Hungary, the opposition Tisza bloc seems to have passed its peak, and Fidesz is consistently gathering strength ahead of the April elections, despite the game of manipulated polls being played against Orbán’s party, which is well known in many countries in the region.

In Poland, following the victory of right-wing candidate Karol Nawrocki in the presidential election, which I wrote about in Brussels Signal two weeks ago, the right wing may be thinking about returning to power in 2027 or earlier.

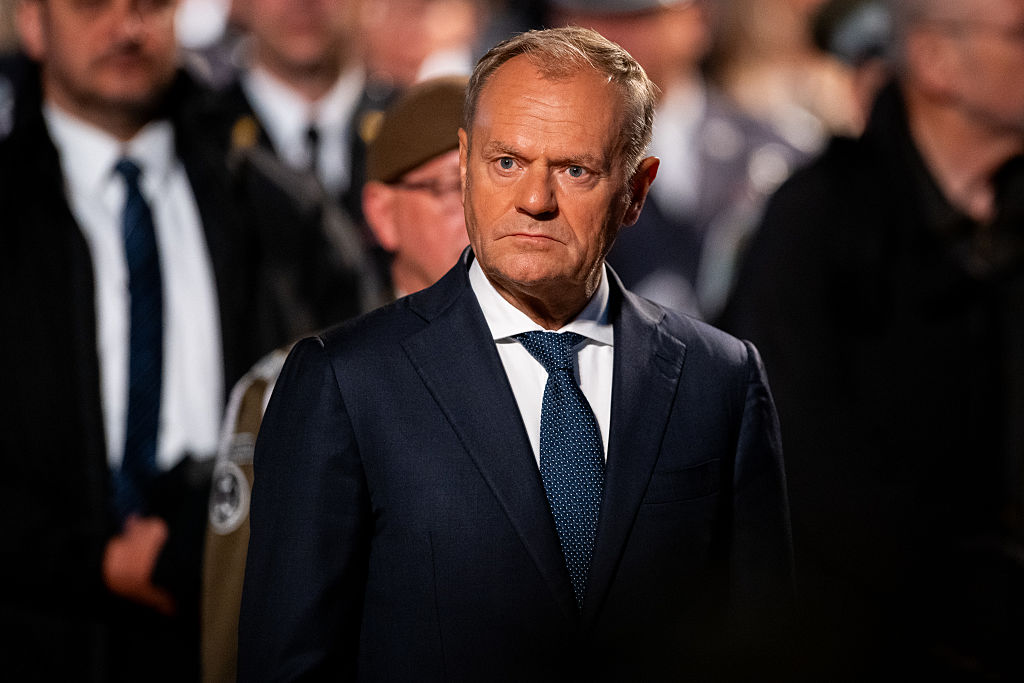

However, even with Donald Tusk as prime minister, a return of the Visegrad Group is already possible. This is because the Polish prime minister, in an attempt to save himself from a decline in support, is clearly turning to the Right. He officially assures that no migrants will enter Poland under the EU Migration Pact, criticises the Green Deal, and has abandoned left-wing social slogans.

My sources in the Presidential Palace say that the newly elected president, Karol Nawrocki, is also looking for some form of renewal of Visegrad cooperation.

When I ask Polish politicians specialising in foreign affairs whether it would be beneficial for Tusk to revive the now almost dead Visegrad Group, they do not rule it out. Tusk has learned well from Angela Merkel how to adopt other people’s slogans, programmes and institutions. Tusk’s attempt to break through to the EU’s decision-making table on his own has also failed. Despite the sentiment towards him from the EU establishment, at no point has he been given even a semblance of real influence, whether in internal EU affairs or, for example, Ukraine. Instead, he was subjected to humiliations, such as being seated in a separate train carriage during a trip by leaders to Ukraine.

Formally initiated in 1991, the Visegrad Group has undergone various periods. Born as a tool to pressure the West to open up to the former communist countries, around 2015 it became a common platform for the Central European region to exert pressure on Brussels. I have observed the group’s meetings up close and it has always been a fascinating experience.

On the one hand, we had a strong community defending common sense, built around the principles of effective border protection against illegal migration, support for economic development, rejection of ideological projects such as the Green Deal, and aversion to social experiments.

On the other, there were real conflicts of interest over attitudes towards Russia and Germany, historical grievances, and conflicts between states. For example, in 2021, a fierce dispute erupted over the Polish Turów mine, located in a coal-rich area on the border between Poland, the Czech Republic and Germany. It was useful for Prime Minister Babiš to support the Czech allegations of environmental damage allegedly caused by the Polish mine. The case went to the European courts, which ordered the mine, and the power plant automatically associated with it, to be closed. For the then Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, it was a matter of honour to defend the plant, which supplied four per cent of the country’s energy. The conflict quickly escalated, but this did not disrupt the activities of the V4 in any way.

The rule there was simple: We discuss what unites us and leave what divides us too much outside the door. It was, of course, a forum that allowed difficult bilateral issues to be discussed face to face. The meetings of the Group’s ministers played an important role. So did the organisation of meetings in smaller towns, often with a rich history during the Austro-Hungarian Empire, such as Przemyśl in Poland. This revived often forgotten layers of shared history. For local communities, these were historic events, commemorated even with plaques on buildings.

The contemporary strength and political prestige of the four countries was built by meetings with the leaders of other countries, such as Turkey and Israel.

From Brussels’ point of view, the picture was not so rosy. The V4 appeared to be a constant source of unrest, opposition, and different ideological and substantive proposals.

It is no surprise that in the package of liberal takeovers that took place in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland, abandoning the V4 was perhaps not written in capital letters, but it was certainly one of the priorities.

However, geopolitics has its own rules. For nation states with a strong identity and memory of communism, which is highly resistant to attempts to impose ideology over common sense, regional cooperation is a necessity. If political penalties are arranged properly, the Visegrad format will return to the forefront.

”From our perspective, Karol Nawrocki’s victory has opened up an opportunity for the renewal of Central European cooperation. We call it the Visegrad Group, but we can call it whatever we want. The key is cooperation, which has been a great success. It worked very well with Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš and Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico. France and Germany had to agree with us on important European issues. Without the Visegrad Group, without cooperation in the region, this would be impossible”, Prime Minister Orbán emphasised in the mentioned July interview.

From the point of view of the region’s citizens, it is worth keeping our fingers crossed. Cooperation in Central Europe is not the answer to all the challenges and problems facing the EU, but when this engine, and sometimes brake, is missing, there is a clear lack of common sense.

Right says No: Ukrainian refugees want to vote in Poland and they want to vote Left