In my favourite park in Warsaw’s Bródno district, I like to sit on a bench with a cup of coffee after my Saturday morning running workout. You don’t have to be nosy to quickly notice that every third family with children passing by speaks Russian or Ukrainian. Every second delivery courier you meet in your everyday life, every third salesperson, every fourth cleaning lady does, too.

According to a CBOS survey from October 2024, about 61 per cent of respondents admitted that they know personally a Ukrainian person.

The million-strong group of Ukrainians living in Poland, as well as the 150,000-strong group of Belarusians, are young, hard-working and ambitious. More and more of them speak Polish well, and the market for Polish language schools and courses is booming. In many companies, refugees and migrants are pursuing successful careers, such as Nadia, my 30-year-old friend from Sumy, who works for a large real estate company. She is committed, willing to work overtime, and is appreciated. Andrei from Kiev, a 45-year-old engineer, came to Poland before the war and works for an IT company, where he is responsible for the important project. He has just bought a new flat.

Andrei recently experienced an unpleasant situation: A group of Poles asked him directly why he was not on the frontline? He didn’t answer, but he tells me that he has a wife, children and a life here. And that no one can demand heroism from anyone, and he is not cut out to be a hero. “There’s a meat grinder there, everyone knows that,” he states.

This topic, related to the discussion about the possible deployment of Western troops to Ukraine, also appeared in the recent election campaign. A clip, for which no one claimed responsibility, consisted of three scenes. In the first, a group of young Ukrainians were dancing in the club to techno music. The second showed young Poles in military uniforms travelling to the Ukrainian front, then fighting there. The third showed their return – coffins, solemnly covered with national flags.

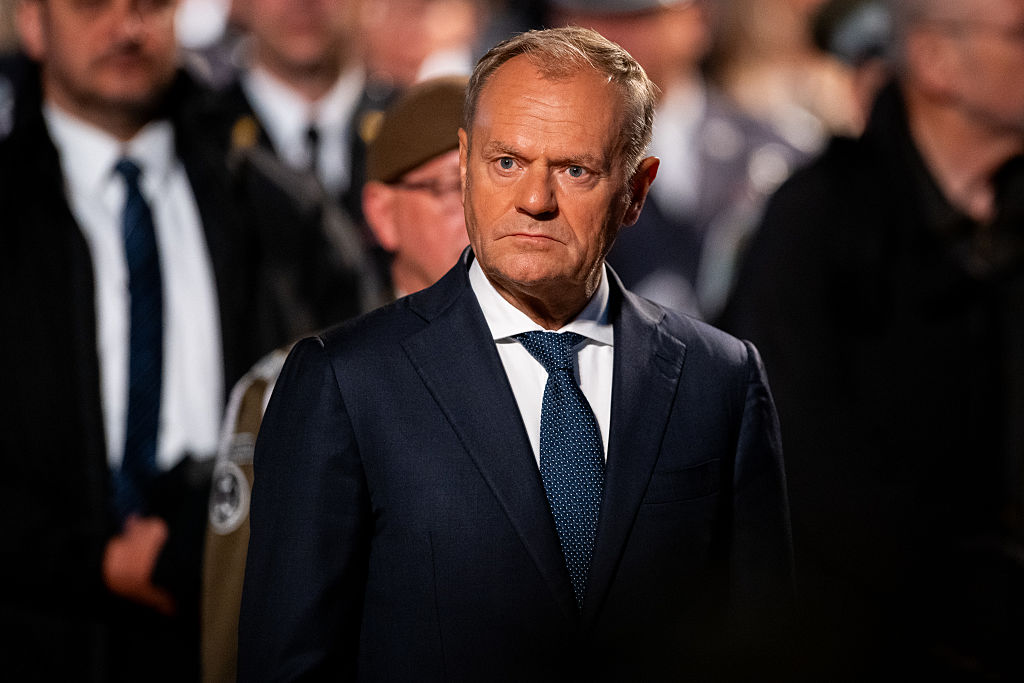

The election campaign was a time of great tension over the presence of Ukrainians in Poland. The wave of hostility was so strong that even representatives of left-wing liberal parties declared the need to limit social benefits for Ukrainians. Rafał Trzaskowski, the ultimately unsuccessful candidate and mayor of Warsaw, put forward such slogans, much to the disappointment of some of his supporters. But it was the later president, Karol Nawrocki, who best summed up the public sentiment, stating succinctly that “Poland will not be Ukraine’s auxiliary farm”.

After the presentation of the survey results, one of my friends who is a public opinion poll specialist sighed and said: “It seems that the only thing that unites Poles today is their disappointment of Ukrainians.”

After the campaign, emotions came down. But the consequences are tangible: The government’s family support programme, which provides PLN 800 (€188) for each child, has been available since October only to foreigners officially working in Poland.

Many experts are asking what happened to the wave of compassion and assistance with which Poles welcomed refugees from Ukraine after the outbreak of war in February 2022. The global media noted with surprise the lack of refugee camps at the time: Most Poles simply took them from the border and brought them into their homes.

Perhaps we need to look at the issue differently. February 2022 was a beautiful act of solidarity, also resulting from the Poles’ own feeling of threat. However, that time was not able to erase permanently conflicts that had been going on for hundreds of years. During World War II, fierce fighting took place in the areas inhabited by both nations and under German occupation. They ended in a series of murders known as the Volhynia massacre, in which Ukrainian armed groups brutally murdered 100,000 Poles. The retaliatory actions of Polish self-defence groups were much less severe.

This wound had no chance to heal because Ukraine blocks (with few exceptions) the possibility of exhuming and giving the victims a dignified burial. It did not change its attitude even after Russian aggression and receiving powerful assistance from Poland, which was important immediately after the outbreak of the war, at the moment of greatest danger. Poland sent over 300 tanks, 11 helicopters, 400 combat vehicles, 54 self-propelled howitzers, mortars, light weapons, ammunition and a lot of other equipment, as well as economic aid.

Many Poles believe that the Ukrainian side has not shown sufficient gratitude. And wherever there is a conflict of interest, such as in the case of grain, which flooded the Polish market as a result of the Russian blockade, it strikes with shocking brutality. Even former President Andrzej Duda, Ukraine’s greatest advocate, heard from President Volodymyr Zelensky at the UN General Assembly in September 2023 that he was “helping to set the stage for an actor from Moscow.” This was taken as an insult. In foreign policy, Kyiv has clearly focused on Germany and France. In the 2023 Polish parliamentary elections, it clearly supported Donald Tusk.

The effects are visible in polls. In 2022, 82 per cent of Poles surveyed had a positive opinion of Ukrainians. In December last year, this figure was 23 per cent.

Anti-Ukrainian content is gaining popularity on social media. There is also another side to the coin. I looked through recordings made by Ukrainians themselves. The ranking of the most hostile societies towards Ukraine? Poland is in first place. Where is it worth emigrating to? “Don’t go to Poland, they just hate us here.” In 2022, 83 per cent of Ukrainians declared a positive attitude towards Poland. At the end of 2024, only 41 per cent. But an important addition: This in no way means an increase in the almost non-existent sympathy for Russia.

The frustration of refugees from Ukraine is exacerbated by the difficulty of obtaining citizenship. At the same time, there are increasing calls for them to be granted full political rights. The Association of Ukrainians in Poland has demanded that all legal economic migrants be allowed to vote in local elections. “People are treated as a labour force that should not have any rights. This is discrimination,’ said Mirosław Skórka, president of the Association of Ukrainians in Poland.

The Ukrainian portal European Pravda wrote recently that the immigrant community, numbering over a million, is increasingly contributing to “Polish prosperity” and deserves to have an influence on Polish politics. “If Ukrainians living in Poland were given the right to vote, they could have their representatives in the Sejm as early as the 2027 parliamentary elections,” the author claims.

Politicians on the Left supported this proposal. Agriculture Minister Czesław Siekierski (PSL) commented that “it does not always have to be related to citizenship, but rather a form that would confirm their functioning here.”

Right-wing politicians are opposed to this. They point out that Polish citizenship is a great privilege and there is no reason to give it to anyone who wants it.

These arguments may be sincere, but they do not reflect the essence of the dispute. The Left knows that migrants always vote for the Left in the first generations, everywhere. This is what the Right fears. We know little about the views of Ukrainians and Belarusians living in Poland, but a review of their media indicates that progressive attitudes dominate, for example on abortion and LGBT issues. Due to their experiences, they also tend to view the European Union uncritically, as an oasis of security and prosperity. The dispute over the limits of the Brussels bureaucracy’s power is completely incomprehensible to them.

Therefore, I have no doubt that if they had had the right to vote, Rafał Trzaskowski would have won the presidential election, not Karol Nawrocki. And that is why, although tensions over voting rights for Ukrainians and Belarusians will grow over time, the right-wing will do everything in its power to prevent the existing restrictions from being relaxed. This will become an increasingly important topic of dispute.

The right-wing in Poland ready to return to power: When? Will anyone betray them?