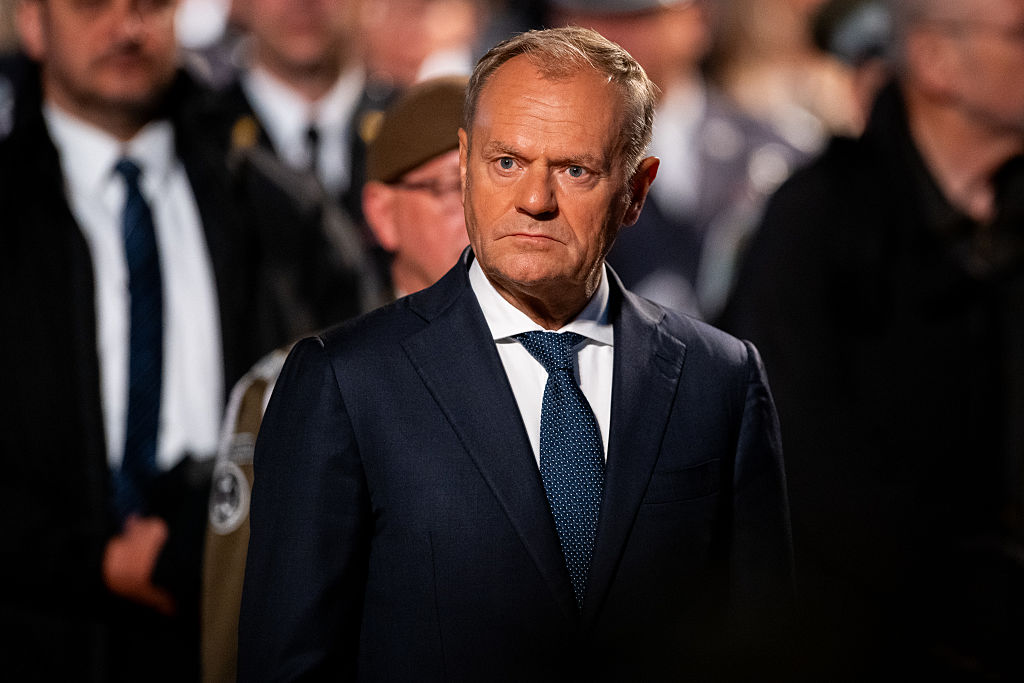

A few days ago, Polish Sejm Marshal Szymon Hołownia, the speaker of the lower house, asked in the parliamentary chamber whether Prime Minister Donald Tusk wanted to take the floor. When the leader of the coalition to which both belong replied in the negative, Hołownia made a malicous comment: “So I was wrong? I’m sorry, it’s high time to leave in disgrace.” The Marshal may have been talking about himself, but most observers considered he was referring to the head of government.

This is just one of the minor elements of the political spectacle we have been watching in Poland since the presidential election, which on June 1 finally decided the triumph of Karol Nawrocki, the candidate chosen by the conservative camp of Jarosław Kaczyński, and the defeat of Tusk’s candidate, the liberal mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski. It was an earthquake that was obvious to cause aftershocks.

The ruling coalition, which took power in 2023 ousting Conservative Law and Justice, is bursting at the seams and rapidly losing public support. It is more and more often losing votes in parliament, although so far on issues that are not of the great importance. In September, even according to the government’s public opinion research centre CBOS, 46 per cent of those surveyed declared themselves to be opponents of the government, while only 29 per cent declared themselves to be its supporters. Never before has the level of support for this government fallen below 30 per cent.

Opinion polls indicate that if elections were held today, Tusk’s coalition partners — the Left, the rural Polish People’s Party (PSL) and Hołownia’s liberal Polska 2050 party — might not exceed the 5 per cent threshold required to enter the Sejm. The prime minister’s party, the Civic Coalition, could count on around 30 per cent, but this result would be at the expense of its coalition partners and would not be enough to continue in power. Law and Justice could expect a similar result. The right-wing but economically liberal Confederation would receive around 15 per cent of the vote, and according to some polls, even more.

In Polish politics, where since the entry into force of the 1997 Constitution changes of governments are rare compared to many countries in Europe, and usually predictable, these signals are interpreted as a indicator of the right’s return to power. Signals from political activists in districts far from Warsaw indicate that there, where they feel the mood of the people best, the local elites of the ruling camp are already preparing for a soft landing after the change of power.

Some are placing their hopes in a change of prime minister. The idea of replacing Donald Tusk with Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski is being seriously considered in ruling circles. The problem is Sikorski’s instability, as he seems to be addicted to causing scandals with his statements every few weeks.

There is also rumour in political circles about the possibility of a change in the coalition during this parliamentary term. This could happen through the appointment of a technical government supported by Law and Justice, the Peasant Party and Hołownia’s party. However, this would be difficult to achieve and would only be possible in the event of some additional crisis. Besides, it is simply not profitable for Law and Justice. The leader of this formation, Jarosław Kaczyński, would probably prefer to wait for the elections and take a full prize.

Paradoxically, when Tusk removed Kaczyński’s team in 2023, he presented himself as the saviour of liberal Europe, capable of defeating, as he described it, right-wing populists. Kaczyński’s eight years in power were supposed to be a sad episode after which things in Poland and throughout Europe would return to “normal”. But things turned out differently, and today it looks like Tusk’s counter-revolution will be just an episode in the midst of right-wing rule in Poland. Importantly, the right-wing that would take power after the next elections, planned for 2027, would be much more more radical and younger. The clear influence of Donald Trump’s political movement, with which he has close contacts in various fields, is evident here.

The desperate prime minister is trying various tricks. He is organising a competition to name a new Polish national sailing ship. He boasts economic growth, but remains silent about the tragic state of the budget and public finances, with Polish debt growing at an alarming rate. He has completely changed course on migration. When he was running for office, he attacked the Law and Justice government for building a barrier on the border with Belarus. He said that there were coming to Poland ‘poor people looking for their place on earth’. Today, he is announcing the construction of an even more powerful barrier and using harsher language against illegal migration. However, it is unclear what his real attitude towards the EU Migration Pact is. He is probably under pressure from his European allies here.

Representatives of conservative media are no longer forcibly ejected from meetings of ruling party politicians. Tusk has clearly decided that, two years after taking power and attempting to restore the liberal camp’s complete monopoly on information, there is no chance of this happening.

The world has changed, and even the most sympathetic journalists working for the public broadcaster, which has been taken over forcibly and illegally by the police, are unable to turn the tide. As everywhere else, social media reigns supreme. And here, the right-wing has been much better in recent years. Deprived of large amounts of advertising money (because of blockades), it organises fundraisers among voters, efficiently builds internet channels, and boldly uses tools such as artificial intelligence. In the past, in order to record a song supporting a right-wing candidate, it was necessary to persuade a singer, who was usually afraid to do so. Today, one can ask one of the artificial intelligences to do so. It may seem like a minor issue, but it has changed a lot in the political arena.

The Confederation party is particularly active on the internet. As a reward, it enjoys record support among young people. But Confederation is a very diverse group. Torn by constant secessions, it currently consists of two main groups: Those opposed to the EU and the left-wing ideology but fierce economic liberals led by Sławomir Mentzen, and members of national movement led by Krzysztof Bosak. The latter are natural coalition partners for Law and Justice. The first not. They contest Kaczyński’s party for its social sensitivity, its policy of large state investments and its policy of restrictions during the pandemic.

During the presidential campaign, Mentzen hesitated for a long time over whom to support before the second round of elections: Nawrocki or Trzaskowski. He himself won almost 3 million votes (14.81 per cent). He tried to manoeuvre, arranged to have a public beer with Trzaskowski and signed a programme agreement with Nawrocki. Ultimately, he leaned more towards the right-wing candidate.

But it was not as clear-cut as it was supposed to be. And it’s an indication that Mentzen’s group may go with Tusk after the next election. Especially with the new Tusk, who is now rhetorically turning to the Right and may economically be returning to liberal slogans. For most voters, this is unimaginable today, but quite possible.

One thing is certain. If you hear reports from Poland in the next two years, they will not sound pleasant to Brussels. Poland is turning sharply to the Right.

EU influence wears off: European court makes a decision, Poland says, “So what?”