At long last, in its 250th year, the American Republic has caught up with its explicitly Roman founding model. The Fathers did not beat around the bush: From the Capitol to the Constitution, the symbolic and practical political DNA of the United States is an SPQR clone modulated by liberal Enlightenment ideas. Even the Federalist debates that lie at the heart of what became the US system of government were conducted under Roman pseudonyms. The Reaganite image of America as the “shining city upon a hill” has caught on so well because it is both a biblical reference (Matthew 5:14) bound up with the Puritan settling of the New World, and an echo of the classic description of ancient Rome as the “city of the seven hills”.

Rome as the supreme expression of power, glory, civilisation and world dominion, as the pinnacle of the arts of governance and statecraft: This was the ultimate vision of America’s founding patres and their long-term ambition for the “senate [well, Congress] and the people” of the 13 colonies in their newly-gained independent-statehood form. The strength of these hopes and the clarity of this vision might have varied from one early US statesman to another, but, overall, the Roman imperative that lies at the heart of the United States is unmistakable and unquestionable.

Re-creating the glory of Rome in a modern setting was never going to be a straightforward process, nor was the final destination ever supposed to be a 1:1 copy of the old res publica. After all, a few rather significant developments had occurred in the intervening two thousand years or so, from Christianity to liberalism with its outgrowths in the fields of economics, politics and law, including international law. Even slavery – so central to the ancient city – had to go at one point. America’s journey towards its pre-ordained Roman destiny could only ever be, therefore, a rather messy and complicated story. But now, under Trump, it seems to have finally arrived.

This is the inevitable end-point of the American project; there was never any other, non-imperial, path that a nation set up on such foundations could have followed. Even George Washington, who famously cautioned the young American state against foreign “entanglements”, in private called the US an “infant empire”. What he likely really meant by his injunction against overseas expansion was that the immensity of the American continent would suffice to build the New Rome envisaged by him and his Founding companions. He was technically correct: Present day USA, with its roughly 9.1 million square kilometres is about twice the size of the Roman Empire at its maximum extent under Trajan.

Washington’s successors, of course, took different views on the foreign question, driven by different circumstances at different times. America seems to have acquired imperial-like influence and weight in world affairs by dint of rising to superpower status almost unwittingly – by responding to great events, like the First and Second World Wars, and then following its newfound “responsibilities”. Or was this rise quite so unwitting? Did the US gain its informal empire “in a fit of absence of mind” as has been said of Britain’s? Or has America been simply trying to deny – to itself and to others – its own nature, in an effort to fit its deeper instincts with those of a lighter and more generous outlook?

All through the quarter-millennium of American history, in practical terms abroad or in the domestic debates at home, the question of empire has never really been a matter of formal overseas conquest and institutional rule. At most, it has been one of informal control – through political, military and economic means, i.e. through hard power translated as “influence” – and of legal and regulatory reach, brought to its highest pitch in recent years through the heavy use of international sanctions. Of course, even Maduro’s “arrest” is not simply a cynical “legal pretext” for the exercise of raw power but a direct derivative of America’s understanding and assertion of the extent and reach of its own laws, in turn shaped by an ever-strengthening imperial ethos.

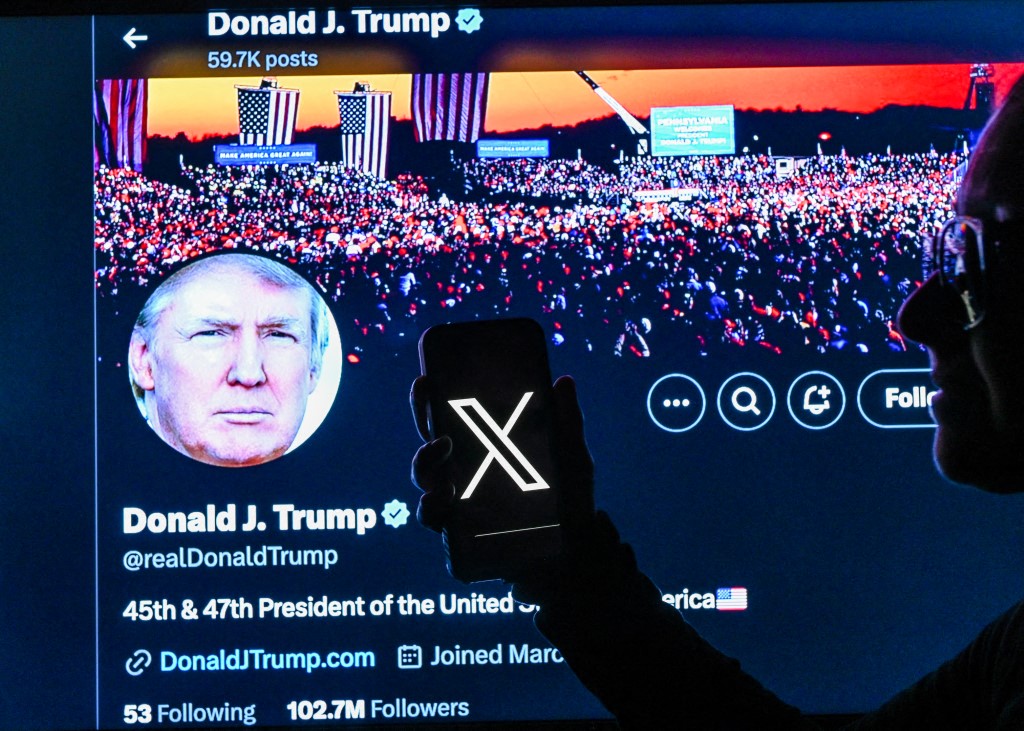

The second presidency of Donald Trump is a neat marker on the US timeline for the overt – if not yet legally formalised – imperial conversion of the American Republic. That Trump has assumed the role of a modern Caesar can hardly be denied. From his political career at the head of the populares party of our day – the MAGA movement – to the enthralling dramatics of this life – including his brush with death in 2024 – and to the late-republican, semi-royal, heavy-handed style of his court and government, in so many ways – though by no means in all – Donald is Iulius returned in the TikTok age. The instinct for foreign territorial expansion or control – Gaul and Britannia for Caesar; Venezuela and Greenland, or the “Hemisphere”, for Trump – as that for securing the loyalty of the military – with Trump even building his own ICE army – are common to both characters. The only major missing piece from this Plutarchian parallel of lives is civil war – but there is still time even for that. The 21st century version might just simply be FBI-led annihilation of the American Caesar’s entire political opposition, and for good reason too.

Like Caesar, Trump will likely be remembered as an enormously consequential but still transitional figure taking his country from Republic to Empire. The significance of the Venezuelan affair lies in the fact that it was a purely imperial act that required no further justification than American interest and American law. We are now looking at an effectively new actor on the world stage, albeit in the guise of what we knew as “America”, but now operating on a self-contained and self-referential logic, openly declared as such.

Every other instance of US intervention that challenged international rules and law in the past – from the South American adventures of the Cold War to Kosovo to Iraq and so on – was always “justified” in some way, with more or less convincing ideological arguments ranging from “beating the Communists” to “stopping genocide” or to “promoting democracy”. There is now no longer the need to do so, because an imperial polity that recognises itself as such has no need to justify anything with arguments outside its own interests and will.

Needless to say, in this American transformation we are witnessing a colossal displacement of the deepest foundations of international relations. Not only is a new US logic now unlocked – which is already leading to highly disruptive behaviours and policies, as on Greenland – the entire national security architecture of all other intermediary powers (i.e. effectively everyone apart from the other two main actors, Russia and China) is now being called into question.

The view expressed in some quarters that we are back to the “pre-WW1” world, or something like that, is an optimistic one because that was a highly civilised world of alliances that operated on the 1815 Vienna system. Perhaps a better analogy for the overall state of our world today is with the mid- to late 18th century, a time of of the Seven Years’ War (the first globe-spanning conflict, and one that also involved North America), of emerging industrial revolution with its deep dislocations, of mercantilism and imperial expansion but also one of a pre-revolutionary ideological development in Europe.

Combined with an American republic now switching to overt imperial project – a task to be completed by Trump’s successor – the strategic landscape of our times is fast becoming possibly the most interesting and full of geopolitical – indeed, imperial – opportunity in centuries. The world now merely awaits the first great and audacious next-generation leader to emerge with the willpower to take advantage of this situation. It’s usually not a long wait.

Trump is attacking Russia’s global strategy