The savage internal conflict poisoning Libya has been ongoing for more than a decade now. Since 2011’s so-called Arab Spring, when rebels ousted and killed Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, the country has been mired in civil strife spawned by toxic tribal conflict and uncompromising militia rule.

When I speak to Libyans, they claim Gaddafi’s rule had to end, despite the ensuing chaos: his dictatorship had lasted too long and was brutal, corrupt and incompetent. Yet they’re not content with what came after Gaddafi.

The fact that the country has become subject to perceived foreign meddling further exacerbates the situation: from European countries supporting opposing sides of the conflict to Gulf countries using Libya to further their proxy wars and increase their influence over the Arab world.

The European Union has failed to help stabilise the country, despite the proximity to its shores. At the start of the conflict in 2011, Europe had the opportunity to forestall a disaster. Instead, the ad hoc military attacks in tandem with the Nato operation against Gaddafi’s forces were a catalyst to Libya’s resulting decade-long conflict.

Europe is paying the highest price for Libya’s instability. The chaos in Libya is having a dangerous ripple effect on the continent: human trafficking, leading to indiscriminate mass migration, being the most prominent. Without dramatic action, Libya represents an existential threat to the stability of Europe.

The rise of European populism – which liberal politicians in Brussels so lament – finds its roots in Libya’s civil war: if the country had a reliable government, the migrant crisis would not have occurred. At the time of Gaddafi’s rule, an agreement was reached with Europe, and in particular Italy, to stop the influx.

Unlike the Middle East, where many refugees were fleeing war, Libya became a transit country for mostly Sub-Saharan African migrants seeking better economic opportunities, rather than those escaping persecution. Accepting these migrants is much more difficult for Brussels to justify to European populations becoming increasingly intolerant to new arrivals.

Libya needs to be unified again for the war to end. This would enable Europe to take a break from the migrant crisis and manage the hundreds of thousands who have already landed on its shores. European politicians need to study the conflict carefully and come up with a solution they all can agree on.

In Libya, the region of Tripolitania in the west is controlled by the Tripoli government, the region of Cyrenaica in the east is controlled by forces loyal to Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, and the region of Fezzan in the south is controlled by the Tuareg, Tebu and Awlad-Sliman tribes. This is hardly an easy map of players to manage successfully.

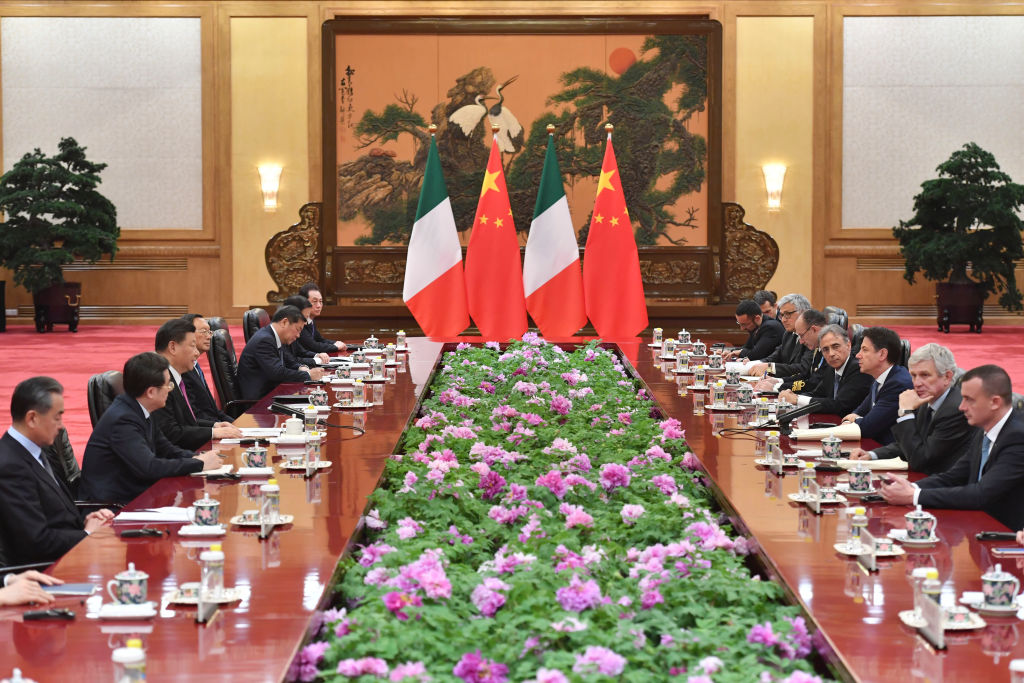

Libya’s Byzantine-style divisions have been unified before. But this will not happen again as long as foreign countries continue to support different factions. In Europe, France is backing Haftar, while Italy and Brussels have so far put their weight behind the UN-recognised government in Tripoli, first called the Government of National Accord, and now the Government of National Unity.

But the Tripoli authority is hardly a government at all; it relies on the loyalty of various rogue militias to survive, and funds from Brussels. All too often those funds end up in the hands of the same militias that are causing chaos. The Tripoli government has proven to be incredibly weak at managing criminal cartels and human traffickers.

The rival eastern forces, on the other hand, are controlled by Haftar, an old Gaddafi acquaintance who decided to collaborate with the CIA. He returned to Libya during the war to develop his own force made up of a patchwork of militias, called the Libyan National Army. This serves as the military wing of the House of Representatives in Tobruk, in the east.

Europe and the West at large overestimated the chances of a democratic transition in Libya. The EU will probably continue to fail to positively influence the country without a long-term strategy. Such a strategy must take proper account of the differing factions in Libya to reach a unified agreement for a democratic national election, which will see one party finally win. An elected government would have true authority because Libyans would have chosen it.

But some factions cannot be legitimised, namely those that continue to sow instability: these include extremist groups and rogue militias. While Haftar, who has until now been received with scepticism from Brussels, must be seen as a legitimate player necessary for any solution to the conflict.

The only way that Brussels can save Libya from its prolonged conflict is to bring all factions to the table and agree on a general election that will legitimise the next leader.

This includes placing financial sanctions on power-players blocking the process, regardless of their faction, rather than doing business with them. Libyan leaders who welcome the process should be supported, including the government in Tripoli, Haftar’s forces, and political representatives.

In the long run, democratic institutions in Libya need support from the EU. For now, Brussels must end its unequivocal support of the Tripoli government, which only survives with backing from militias it bribes to keep it in place.

A more intelligent approach might finally unify the country and achieve peace.

Alessandra Bocchi is Associate Editor at Brussels Signal

Will Erdogan repatriate a million Syrian refugees?