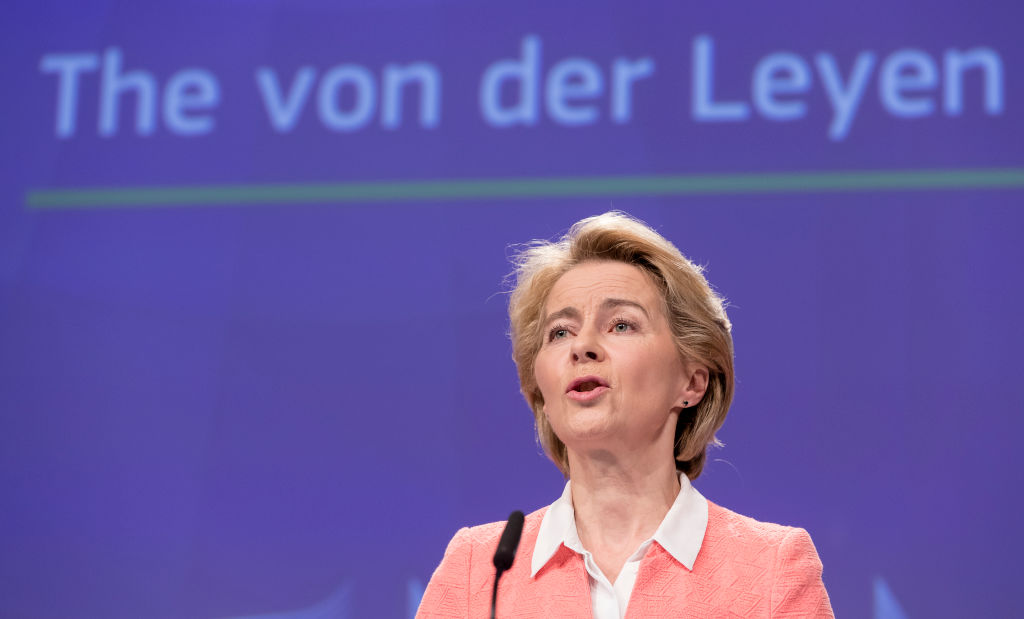

“Renewables are cheap, they are home-grown, they make us independent.” – with these words Ursula von der Leyen, the powerful President of the European Commission, announced that the Green Deal will play a key role not only in Europe’s climate policy, but also in its approach to security. Learning from the war in Ukraine, the EU is determined to end its dependency on foreign energy sources, particularly fossil fuels supplied by authoritarian regimes.

The EU’s preferred way of achieving this goal is the “electrification of the economy and the greater use of renewable energy,” primarily wind and solar. While it is easy to make plans, the question is whether they can be achieved. Let us take a closer look at the promised national security implications of the energy transition. Wind and solar seem to be commendable alternatives to fossil fuels, because while a few nations can control the supply of oil and gas, no country can yet command the wind and sun. Unfortunately, the case becomes less persuasiveness once we realise that the energy contained in wind velocity and sun rays needs to be harnessed and transformed into electricity, two processes that are more resource intensive than the European Green strategy is willing to admit.

A term that will become more widely used in the years to come is “critical minerals” (or “energy minerals”), the numerous raw materials necessary to produce clean energy. And the need for these is substantial: as the International Energy Agency (IEA) has pointed out, “a typical electric car requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant. Since 2010 the average amount of minerals needed for a new unit of power generation capacity has increased by 50 percent as the share of renewables in new investment has risen.”

Clean energy can reduce dependence on coal, oil, and gas but it will simultaneously create new dependencies on different minerals, including copper, zinc, and lithium. The IEA estimates that by 2040 the need for these resources could be four to six times what they are today. Any plan for an energy transition must take the supply of these materials into account. Given the fact that new mining projects take between 10 to 15 years to launch, it is a safe assumption that the main suppliers today will remain the main suppliers in the foreseeable future. Or, to be more precise, the main supplier: China’s global market share in refined energy minerals is twice the Opec market share in oil. As the energy expert Mark Mills, has pointed out, it is not just a question of mining, but also of refining – which is both energy intensive and puts a lot of stress on the environment due to the necessary use of toxic substances in the refining process. Given environmental regulations in Europe, the idea that a large domestic mining and refining industry will emerge in the near future is highly unlikely, as is the idea of a competitive domestic renewables industry.

Not surprisingly, those who control mining and refining also have an advantage in the downstream production chain and control an outsized share of the market. In 2022, 87 per cent of Germany’s imported photovoltaic power stations came from China, and for the EU as a whole, China accounts for over 60 per cent of imported wind turbines and over 80 per cent of photovoltaic technology. Yet the looming dominance goes beyond wind and solar: The proposed energy transition to more electricity will need a massive overhaul of the electric grid, which would have to grow by a factor of at least 4 by 2050 requiring massive amounts of copper, but also so called electrical steel that is crucial for transformers (that lowers the voltage of power from transmission lines so it can be used in households) and EVs. Almost 80 per cent of this crucial component is produced in China, Japan, and South Korea. Out of the ten largest EV battery producers six are from China, three from South Korea, and one from Japan. The heart of future EV production will be in Asia, not Europe, and Chinese companies are already increasing their market share globally and in the EU (up 165 per cent from a year ago). As the Dutch minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation has recently pointed out in an interview with the Financial Times, “Europe’s energy transition is impossible without China.” Mrs von der Leyen should take note, for renewables will be neither cheap, nor home-grown, nor make us independent in the foreseeable future.

Ralph Schoellhammer teaches at Webster University, Vienna

Return of the Reds? The Communist Party achieves another victory in Austrian regional elections