A year before the upcoming elections to the European parliament, a silent revolution seems to be taking place in Europe: Right-wing populists are learning to actually enact policies and not just harness popular anger before they implode once they get into power. The question is, will these movements be able to withstand the growing attacks of Europe’s mostly Left-leaning media?

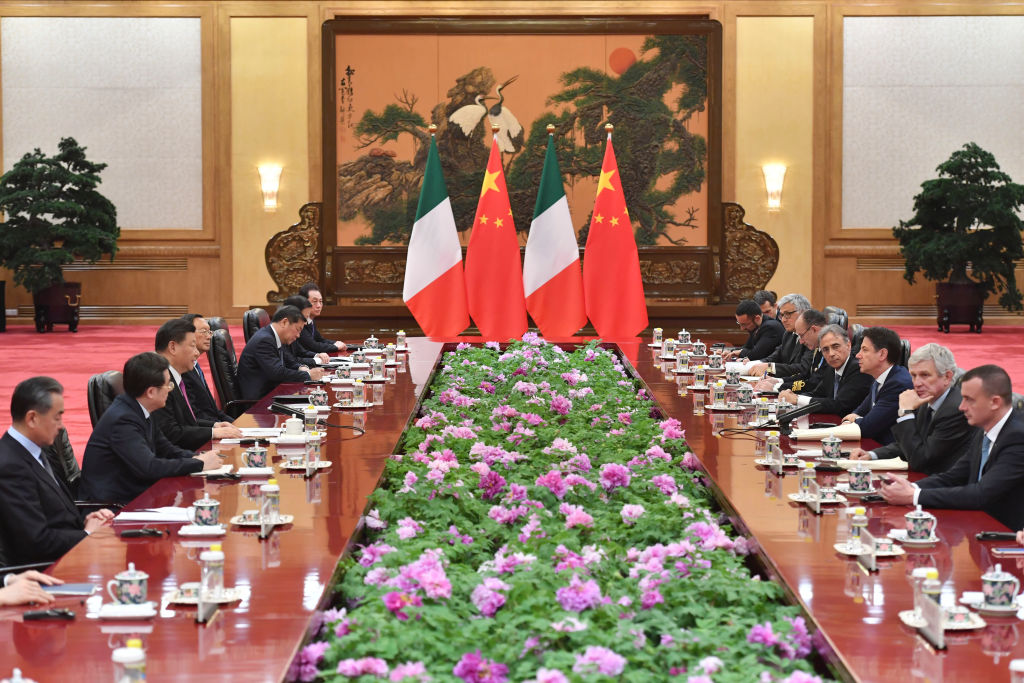

Giorgia Meloni’s Italy could be an example of how to do it: Her government has been making headlines for her Right-wing stance on a variety of issues from welfare reforms, new immigration policies, to climate change. It has simultaneously been one of the most staunch defenders of the transatlantic alliance and an unwavering supporter of Ukraine.

Not all policies are well thought through – like the recent idea of a windfall tax on banks – but in historical comparison Italy seems to finally have a government that knows what it is doing.

After coming to power on the national level in 2022, the Right wing bloc was winning a landslide victory in regional elections in February 2023, vindicating Meloni’s course. Polls show that since the general election in 2022 support for her Brothers of Italy party remains high at 30 per cent, demonstrating the political acumen of Meloni.

Although some on the Right are disappointed that Meloni did not become the anti-Globalist or anti-WEF force that they were hoping for, this only shows that she is well aware of political realities.

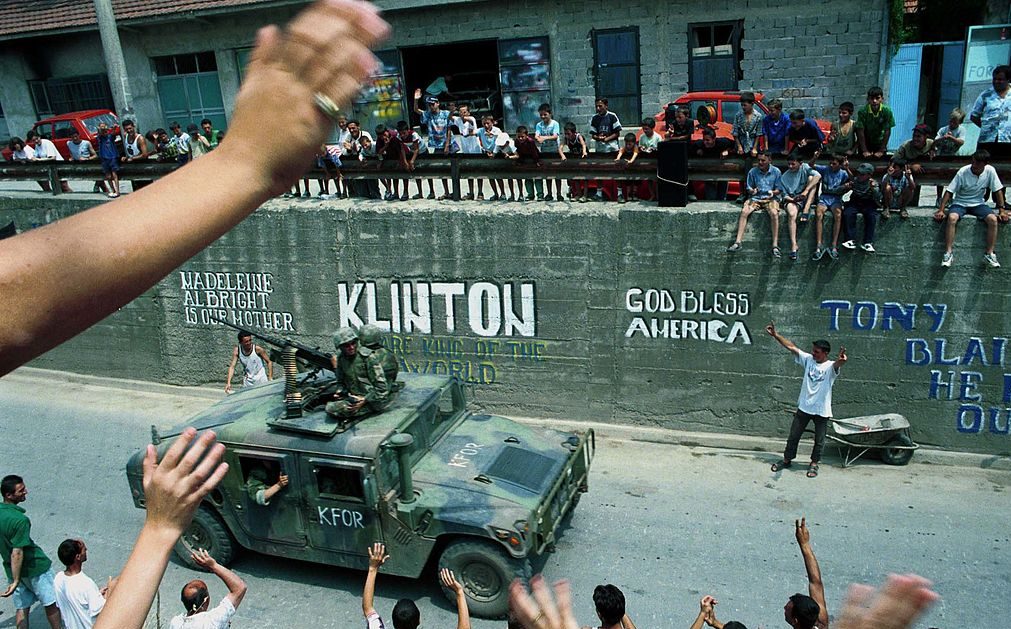

Triangulating between a moderate stance abroad and an increasingly conservative stance at home has so far spared her the treatment experienced by Hungary and Poland, two countries that are under constant pressure from the EU. In the case of Hungary even the US has joined in, recently tightening visa restrictions for Hungarian citizens.

Of course, this will not stop most of the establishment media mobilising against Meloni. The Economist, for example, has recently lamented that Italy’s government is starting “to look more radical” and to engage “in cultural and economic populism”.

The article expressed genuine befuddlement that the conservative government of Meloni would be less enthusiastic about promoting issues like surrogacy for same sex couples or the LGBTQ+ agenda. They are nothing like the Tories in Britain, the author complains – not mentioning that this might be the reason why Meloni leads the polls in her country and why the Tories are sinking in the UK.

Apparently the best way for Right-wing politicians to surprise the Left-wing media is to actually govern according to the promises they made to be elected in the first place.

Now, in defence of The Economist, they were writing about a certain “Georgia Meloni,” while the name of the actual prime minister is “Giorgia Meloni”. Such errors support a suspicion that many have when it comes to reporting about the Right-wing in Europe by mainstream media: It does appear as if they have one ready-to-publish article on every Right of centre movement on the old continent, just switching the names of the main actors.

Every article about the Sweden Democrats, the Austrian Freedom Party, the French National Rally, the Dutch Party for Freedom, the Brothers of Italy, or VOX in Spain follows the same pattern. They are populist, neo-Fascist (or at best post-Fascist) – and generally not to be trusted.

Every news outlet has a right to its own editorial line – but there is a growing trend to confuse reporting with activism. In Bavaria for example, the leader of the popular Free Voters party, Hubert Aiwanger, who is also deputy Prime Minister of the state and in a coalition government with the conservative party, was recently accused by the major newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung of having written an anti-Semitic pamphlet over three decades ago (as Brussels Signal reported).

As it turned out, it was written by his brother during his high-school years and has been available in public archives since 1989, so even the slightest form of journalistic diligence would have revealed the true author. The objective was not truth, but the creation of rumour to make a politician unelectable.

It is surely no coincidence that before the regional elections in Bavaria this October such a story appears in an obvious attempt to take down a successful right-wing movement. The Jewish-German historian Michael Wolffsohn looked through the entire charade and called it what it is: an attempt to destroy someone politically. A sentiment that was also echoed by the Swiss Neue Zürcher Zeitung, who described the entire affair as a campaign against Aiwanger that has little to do with reporting.

Such developments should worry us all. They are a direct threat to the democratic process. If so-called quality media are getting a pass for not being able to correctly spell the name of the Italian Prime Minister or simply making things up, how exactly do we expect the population to be accurately informed?

Presidentialism: What Giorgia Meloni has, and other Right-wing leaders would do well to emulate