When a European leader calls a national referendum he is confident he will win, you should picture the old Road Runner villain Wile E Coyote holding a lit stick of dynamite. Something is about to go horribly wrong.

The latest victim is soon-to-be former Taoiseach Leo Varadkar, who proposed adding new language to the Irish constitution “modernising” references to marriage and the role of women.

David Cameron is only now slinking back into politics after his ill-fated Brexit referendum in 2016. That same fateful year, Matteo Renzi vanished from Italian politics after the failure of his proposed constitutional reforms.

And let’s not forget the reigning grandmaster of referendum misfires, the 2005 votes on the new EU Constitution that failed miserably in France and the Netherlands, two of the founding members of the European project.

In each of these cases, disappointed “Yes” supporters thrashed around in their agony for a justification that did not endanger the presumed virtue of their proposals.

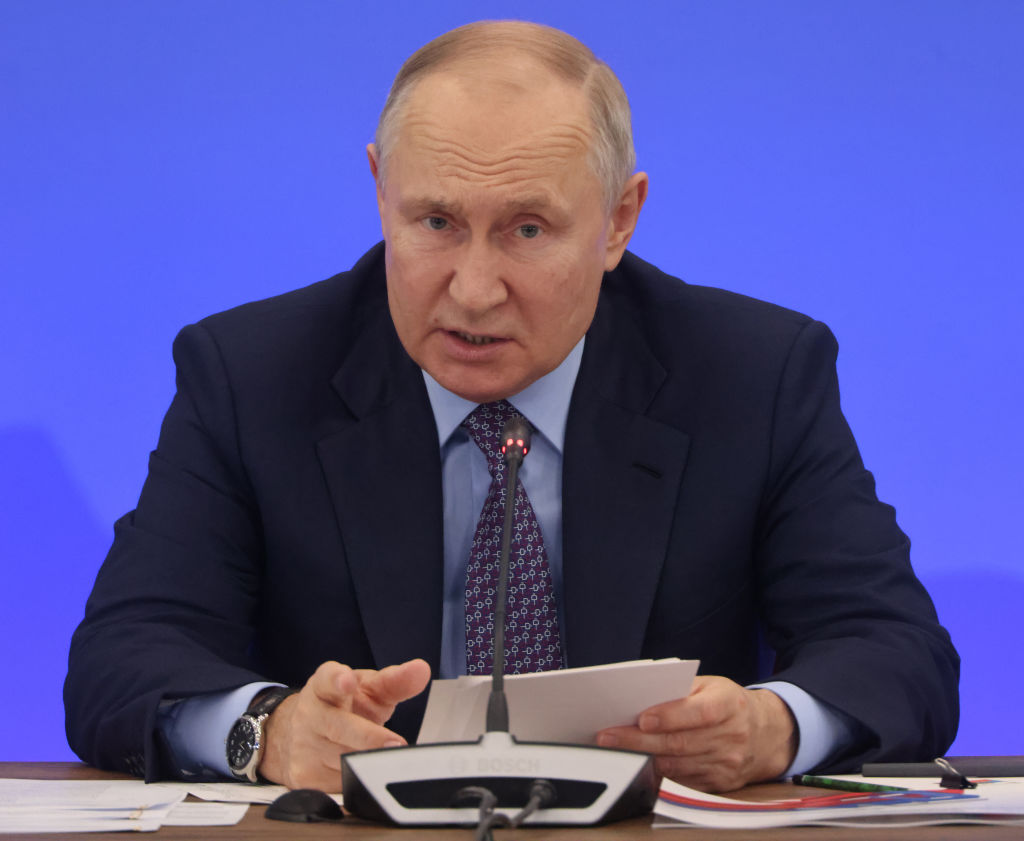

They variously blamed bad timing, poor marketing, voter confusion and (lately) evil misinformation, ideally traceable to the Russians. In no case however, did these proponents consider that voting majorities did exactly what they intended: derail an elite project they viewed dubiously.

Rather than investigate voter motivations, EU leaders have drawn the conclusion that referendums must be avoided at all costs. Yet stifling one avenue of popular expression simply channels discontent into less formal, more disruptive protests.

Hence, the tractors besieging European capitals. The proximate causes of farmer discontent are the new rules imposed by the EU restricting pesticide use, curbing methane emissions, and mandating land set-asides for biodiversity. All these regulations serve the EU’s commitment to a Net Zero agenda, which apparently among other things requires that half the livestock in the Netherlands be slaughtered by 2030.

Many European farmers have understandably lost faith in the wisdom of the EU and do not defer to these new regulations. A loss of voter trust is normally remedied by an election that gives failed leaders the sack. But the European Union lacks this democratic feedback loop by a structure explicitly designed to insulate decisions from popular pressure.

Consider this from the perspective of a disgruntled Dutch farmer. He can vote for his parliamentary representative, who may form part of a multi-party coalition selecting a prime minister, who in turn constitutes one of 27 votes on the EU Council.

No Dutch farmer can vote for the Commission, where all these proposals originate and whose leadership is determined by backroom horse-trading among big EU states. Like most EU citizens, he cannot name his representative in the EU Parliament, and again like most EU citizens he cannot understand how the assembly serves his direct interests.

Deprived of a viable democratic voice by this arcane structure, he takes to his tractor, and may add to the fun by bringing along a full manure spreader.

In response, the EU and several member states have pulled back from several of their more onerous proposals, but clearly more as a holding action than a policy rethink. Soon enough, the thinking goes, the farmers must return to their fields and the EU’s grand project of saving the world from belching cows can resume.

While this may prove accurate, it ignores the EU’s chronic difficulty in channeling popular grievances into effective influence on EU proposals. Ideally, the power to formulate initiatives should move from the Commission to the Parliament, where duly elected representatives can hash out proposals amid all the tawdry aspects of a functioning democracy: lobbyists, angry constituents, ugly compromises.

Nothing would raise the visibility of EU Parliamentarians more than giving them the power to craft laws directly affecting their constituents.

The EU was founded as an elite project by leaders like Robert Schumann and Jean Monnet who had a justified fear of the popular authoritarians who drove Europe to ruin in the 1930s. But a mature Union can now accept a greater institutional role for its citizens.

The alternative may be the radical subsidiarity proposed by Marine Le Pen, which would reduce the European project to its prior role as a modest common market.

If the federalist project is to thrive, it must introduce a direct democratic voice into policy-making. The outdated elitism of the community’s founders is now an obstacle to the legitimacy of the European project.

The EU has a choice: more democracy, or more tractor convoys? The manure-spattered buildings in Brussels serve as a warning.

Can the EU’s strategic ambitions survive its looming fiscal cliff? Without something giving, Europe won’t be able to fund and arm Ukraine