Four years before he became president in 1981, Ronald Reagan announced his Cold War policy: “We win, they lose.” He could not have offered a better depiction of a zero-sum outcome to the conflict, in which Western success required Soviet defeat.

It is worth recalling just how radical Reagan’s statement was at the time. The spirit of detente still ruled in 1977, two years after the joint Apollo-Soyuz mission and two years before the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan ended the thaw in superpower relations.

The engineers of detente eschewed stark zero-sum propositions in favour of mutually beneficial outcomes with the Soviets such as strategic stability, arms control agreements, and a mutual recognition of each superpower’s legitimate spheres of influence.

Sacrificing the freedom of Eastern Europe seemed a reasonable concession if it improved Soviet behavior elsewhere. Reagan’s straightforward alternative proved prescient. The Soviet Union not only lost the Cold War, it collapsed, while the United States endured as the world’s remaining superpower.

There was then and is now a profound bias among the bright sparks in the Western foreign policy establishment in favour of “win-win” compromises.

Conference papers, book publications, entire careers can be fashioned by devising various ingenious proposals to solve conflicts that may in fact be intractable. The lively intellectual repartee needed to forge compromises is much more rewarding than the blunt stubbornness required to prevail in a “win-lose” confrontation.

Civilised people everywhere prefer to solve problems through congenial compromise rather than the imposition of terms on the unwilling. While this tendency is admirable in solving disputes among allies, it is dangerous when confronted with the demands of a foreign adversary determined to win at our expense.

That a top US negotiator started her career as a social worker suggests an institutional preference for empathising with the demands of our adversaries rather than resisting them. When clever diplomatic compromises paper over irreconcilable objectives, you have only postponed the dispute, not solved it.

The 1994 nuclear deal with North Korea stands as a sorry testament to this principle. Kim Jong Il was determined to get nuclear weapons; the Clinton Administration pretended that a negotiated deal had stopped him.

Which of course brings us to Ukraine, a classic zero-sum conflict not amenable to empathetic negotiation. Either Russia subjugates Ukraine, or Kyiv retains her unfettered sovereignty. They cannot both realise their war goals.

The odd Western tactic of doling out just enough aid and weaponry to forestall Ukraine’s defeat is explicable only as part of a tacit strategy bent on preserving the chance for a negotiated compromise with Putin.

Kyiv, the Poles and the Baltic states all recognize this as a chimera: nothing but defeat will disabuse Russia of her neo-imperial fantasies. Any compromise offering up Ukrainian concessions to appease Putin will likely fuel his ambition to try again once sanctions are dropped and Russia can refit her battered forces. Pursuit of negotiated compromise is a delusional objective when one party must lose in order to sate the appetites of its adversary.

The latest attempt at pausing the conflict in Ukraine comes courtesy of Turkish President Recif Erdogan. He proposes freezing the current front line, committing both Russia and Ukraine to mutual “non-interference”, referendums in occupied territories by 2040, Ukrainian non-alignment until 2040, and a commitment by Russia not to oppose Ukrainian membership in the EU.

Erdogan clearly hopes that excluding Ukraine from NATO for 15 years is attractive enough for Putin to accept EU membership for Kiev, and conversely that EU membership is attractive enough to Kyiv to forgo NATO, and accept that its occupied territories will remain lost until 2040 at least.

Erdogan is likely also guessing that the prospect of a major Russian offensive this summer might induce Zelenskyy to negotiate now before he loses any more territory. However, the Turkish President’s proposed compromise is unlikely to persuade the combatants.

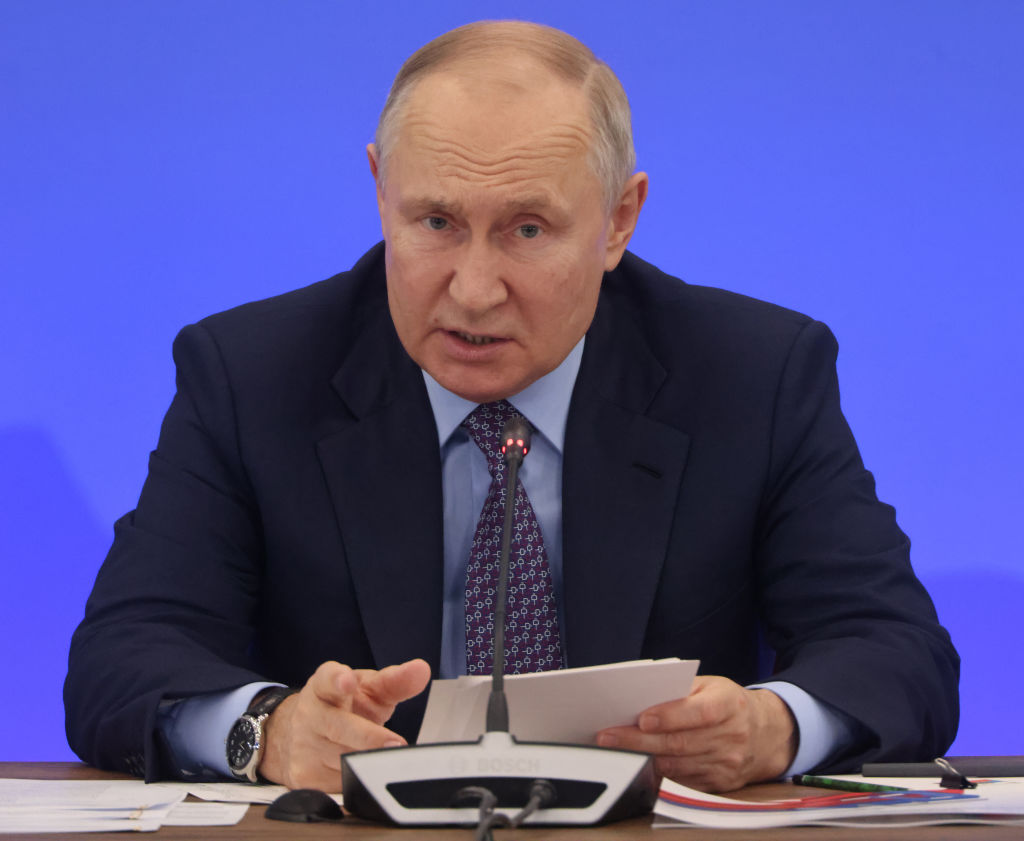

Putin believes he can grind the Ukrainian army down over the coming months or even years if need be. Zelenskyy will not wager his country’s survival on a “non-interference” pledge by Putin and cannot relinquish his oft-stated pledge to reclaim occupied territory and join NATO.

Can any compromise be found when competing war objectives are starkly zero-sum? At best, Erdogan’s proposal would freeze the conflict until such time as Putin is ready to renew it.

Zero-sum military conflicts are usually resolved through war. Japan’s Co-Prosperity Sphere didn’t survive Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the Red Army ended Nazi dominion over Eastern Europe.

The imperial militarism that afflicted both countries was vanquished to the point where reflexive pacifism continues to hinder the development of a healthy strategic culture in both Berlin and Tokyo. If changing the imperial militarism currently loose in Ru requires similar invasion and occupation, then we will not soon rid ourselves of it.

No one in the West intends a general war with a nuclear armed state whose leader has recently threatened the use of these weapons. But the West must recognize that Ukraine is fighting more than the Russian Army. It is fighting an imperial mentality of the sort that drove Germany and Japan to subjugate their neighbours.

It is easy to mistake war as a matter of military strength, industrial capacity, and population, hence the analytical focus on weapons, factory production, and conscription numbers.

But Ukraine is not at war with Russian statistics, it is at war against a deeply rooted national identity that grants Great Russia the right to reclaim its historic domains and lord over its neighbors as the dominant power in Europe.

While Putin has mobilised this national identity in support of his war, surveys showed broad public support for his conception of Great Russia before the invasion. The majority of Russians regard Ukraine as part of Russia, and support the war as a legitimate means of saving the territory from the acquisitive designs of the West.

These beliefs are not particularly subject to material considerations. Russians remain relatively poor compared to the EU citizens, they’ve seen tens of thousands of their young men sacrificed to little effect, and their economic prospects remain bleak as long as Western sanctions isolate them from the bulk of the world economy.

War is draining the Russian nation of wealth, skills and manpower, the loss of which will consign the country to relative poverty for a generation at least. Yet the Great Russian dream remains popular, in part because it is coupled with a highly-developed national victim complex.

Given the history of Russia from the time of the Mongol hordes to the German invasion in 1941, it’s not hard to see why. The popular belief in Russia that the West seeks the destruction of the Russian state is an echo of this historical paranoia and serves as justification for all brutality inflicted on Russia’s adversaries.

Acknowledging that Ukraine is fighting the neo-imperial dreams of Great Russia makes the conflict far less amenable to compromise. Peace will not come from arranging lines on a map and signing attestations of non-interference.

Consider the case of Serbia, which launched wars to reunite “Greater Serbia” and whose people nurse a national victim complex perhaps equal to that of Russia.

The Great Serbian worldview still endures 25 years after the devastation of Belgrade by NATO bomber. Bosnia remains a facsimile of a state thanks to the stubborn irredentism of its Serb minority; Kosovo remains subject to constant threats and covert aggression by Belgrade. Serbia will permit neither Bosnia nor Kosovo to mature into normal European countries even after successive military defeats by the West. Serbia behaves only because it fears NATO and wishes to join the EU.

Given that NATO will never send its bombers to subdue the Kremlin and the EU will never admit Russia, how can we reasonably expect Moscow to relinquish its imperial designs on Ukraine? In short, we can’t. Imperium is an innate component of the orthodox Russian soul, now formally confirmed by Patriarch Kirill.

As Russia will likely remain intoxicated by imperial arrogance, only NATO membership can create the deterrence necessary for a cold but stable peace between Ukraine and Russia. Prompt EU membership will generate a level of prosperity in Ukraine superior to that enjoyed by Russians. Ukrainian economic success will threaten Putin in much the same way that Polish prosperity delegitimises Aleksandr Lukashenko’s rule in neighbouring Belarus.

Short of the unlikely emergence of a true partner for peace in the Kremlin, embedding Ukraine in these two organisations is the best means of securing victory. Denying Ukraine NATO membership in 2008 did nothing to appease Putin or his imperial designs on the country. In launching his invasion, he lost any legitimate claim on Ukraine’s non-aligned status. A prosperous Ukraine anchored in the West means we win, Putin loses, and his military adventure fails.

Can we relearn these hard lessons of zero-sum confrontations? The early decades of the Cold War required a transatlantic dedication to thwarting Soviet ambitions.

Both Mastering this “win-lose” conflict will require strong leadership of a balky alliance, coupled with a policy stubbornness inimical to the managerial instincts of most career diplomats.

Both China and Iran nurse ambitions they can realise only at our expense. They are watching closely to see if Russia can fracture the world’s greatest military alliance and defeat its Ukrainian partner. If Putin succeeds, aggressive warlordism wins as a model for ambitious despots everywhere.

Imagine a replay of the 1930s, with nukes.

The tractor referendums: The EU has a choice – more democracy, or more farmer protests?