Nicole Grünewald, president of the Cologne Chamber of Industry and Commerce (IHK Köln), has dismissed German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s remarks about the state of the country’s economy.

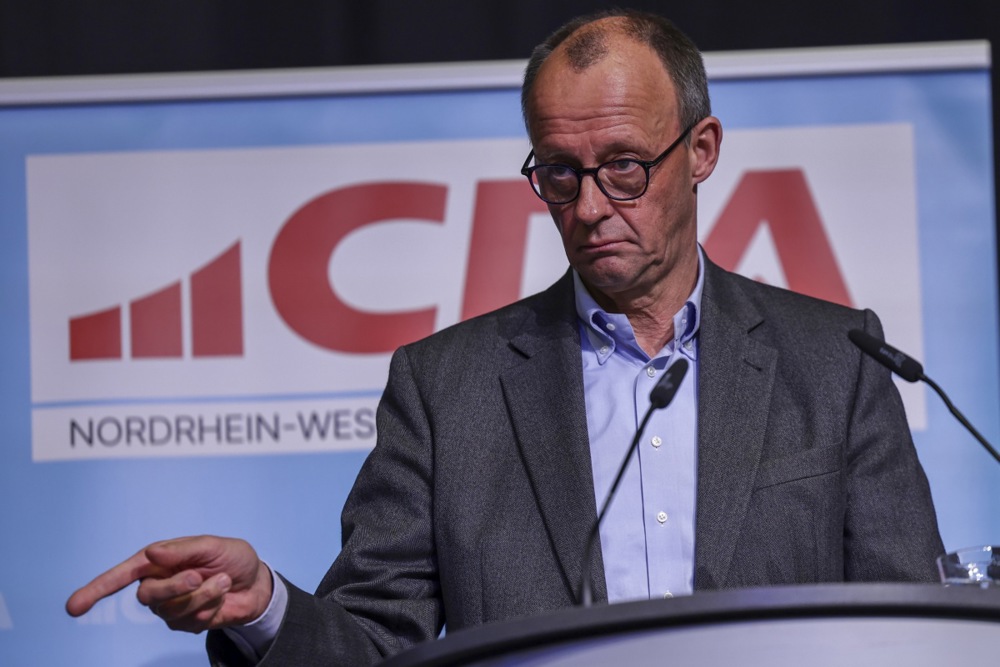

While Scholz glossed over the situation during his TV debate on February 9 with Christian Democratic Union (CDU) opposition leader Friedrich Merz, Grünewald said she saw clear signs of deindustrialisation in the relocation of investments abroad.

Grünewald, who represents 150,000 companies as IHK Köln chief, told media outlet Business Insider that German companies were moving abroad because the country was increasingly seen as an unattractive business location.

During his TV debate with Merz, Scholz claimed that, while the mood about the German economy was down, there was no deindustrialisation.

In reaction to this, Grünewald said: “We see it diametrically differently than Olaf Scholz. And we can’t understand why he claimed the opposite in the TV debate.”

“The fact that an incumbent Chancellor denies ongoing deindustrialisation is a problem for our economy,” she added.

“We live in times of fake news and disinformation. It would help if the Chancellor stuck to the facts. And one fact is: Germany is experiencing deindustrialisation.”

Germany’s economy has continued its downward spiral as official figures revealed almost 3 million people were unemployed in January 2025. https://t.co/iEbT4aqmJo

— Brussels Signal (@brusselssignal) February 3, 2025

Grünewald, who said her organisation conducted regular surveys on the matter, added: “The figures speak for themselves. 29 per cent of companies that operate internationally want to expand their foreign locations.

“At the same time, 34 per cent want to reduce their investments in Germany. This means that our companies are shifting their investments abroad. This is not a snapshot, but a trend.”

She said she relayed the figures to Scholz when he visited her organisation at the beginning of January.

“We told him very directly and backed it up with facts,” she said, noting that one of the largest IHK Köln member companies, Covestro, no longer invested in Germany as a business location because it was not now profitable to do so.

“It doesn’t get any clearer than that. I am therefore stunned that the Federal Chancellor simply does not take note of these facts,” Grünewald stated.

She said the situation was particularly critical in industry, mainly due to steep energy prices that were still twice as high as before the Ukraine war started in 2022.

She also pointed to excessive bureaucracy and high wage costs as problematic.

“Industry in Germany simply no longer produces competitively,” she told Business Insider.

According to her, German businesses needed a reduction in bureaucracy and a “sensible” energy policy after the troubles of COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. She said the progressive traffic-light government had not tackled those issues.

“It was three lost years in which many things could have been steered in the right direction,” Grünewald said.

“While GDP has grown by 5.3 per cent in the EU member states since 2019, it was only 0.3 per cent in Germany. So we need a new start from the new government.

“We need reliability. More than half of our companies now say that they no longer have confidence in politics. We have never had that before: the economy sees politics as a risk factor for Germany as a business location.”

Because people had lost confidence in Germany, they no longer invested there, Grünewald said.

She also referred to the decision to push forward the coal phase-out. “To ensure security, we should use all energy sources.

“The shutdown of the three remaining [nuclear] power plants was wrong. We were shocked when we learned afterwards that it could have continued without any problems,” she said.

Grünewald said industry needed base-load energy – coal, gas or nuclear. She added that the current coal phase-out implied a lot of new gas-fired power plants but that almost no planning applications for these had been put forward or approved.

She pointed out that only one was actually on the drawing board and the building of it would take at least six years in Germany, given all the permits that had to be secured.

COMMENT: For decades, Germany was hailed as the “economic engine of Europe,” boasting industrial prowess and an export-driven economy. However, recent years have revealed cracks in this foundation, writes @BogdanosK. https://t.co/FGdv0TmF5D

— Brussels Signal (@brusselssignal) January 29, 2025