The tobacco industry was not “against regulation or taxation”, according to Philipp Hansen, European affairs director at Japan Tobacco International, “but it has to be predictable and reasonable”.

He said paying more tax was acceptable as long as the European Union harmonised its tax rates.

In March, 11 EU health ministers signed a joint letter urging the European Commission to revise the legislative framework for tobacco control, citing public health risks and the rapid spread of new nicotine products.

Tobacco industry players said they were also in favour of updating the regulations, as the current lack of harmonisation of rules in EU member states regarding tobacco had resulted in fragmentation of the internal market. It also fuelled a surge in the illegal tobacco trade, increasingly orchestrated from within the bloc itself.

Efforts to revise the EU’s two main tobacco laws — the Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) and the Tobacco Excise Tax Directive (TED) — began as early as 2020 but have since stalled.

The current TPD, which regulated areas including packaging, health warnings and product composition, was adopted in 2014 and entered into force in 2016. The TED, which sets minimum excise rates across the bloc, dates back to 2011.

Illicit tobacco production has evolved far beyond small-scale smuggling, according to Hansen. “We’re not talking about someone bringing cigarettes into EU borders to avoid taxes anymore. There are now highly organised operations,” he said, adding gangs once based in Belarus, for example, had relocated manufacturing into the EU.

In the absence of common legislation, member states implemented their own rules, sometimes at the national level, sometimes regional.

But without a common EU framework, enforcement has remained weak. “You can pass a law in one country but if consumers can just drive next door and buy cheaper, untaxed products, the law has little effect,” Hansen said.

While the EC has conducted public consultations and impact assessments, no concrete legislative proposals have followed. Hansen described the situation as “unusual” given that there was strong pressure for such from numerous member states.

In addition, public health advocates and the industry itself have pushed for improved clarity.

Despite that, member states have remained divided. Countries including France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Ireland tended to take measures aimed at limiting use. By contrast, Romania, Greece and Italy, where consumption levels were higher, took a more nuanced position.

This divergence has made it difficult to reach the unanimity required for any changes to EU tax rules.

Compounding the stalemate was political hesitation in Brussels. Other priorities — such as defence, trade and competitiveness — have dominated the agenda of the EC and European Parliament.

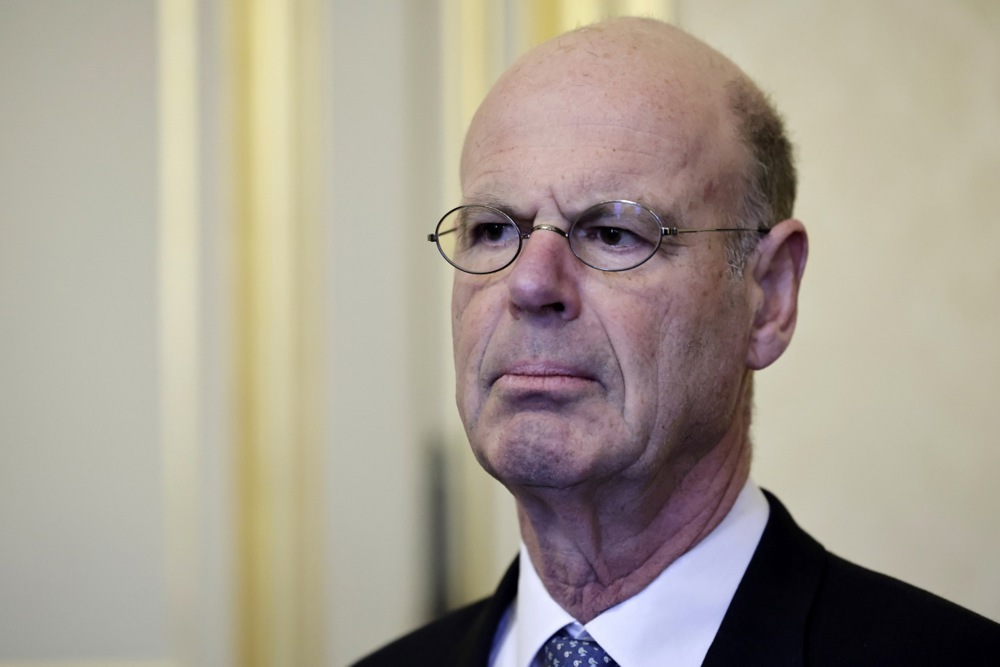

While industry called for clarity and co-ordination, MEPs including Belgian Yvan Verougstraete have been wary of any reform processes becoming too industry-friendly.

“We must first and foremost ensure that a reform of EU tobacco legislation does not go against public health,” Verougstraete, who sits on the European Parliament’s Health Committee, told Brussels Signal.

“Historically, the most Conservative and extreme parties in the Parliament have been very close to tobacco industry lobbies, often repeating their arguments,” he said.

“Public health is not a topic to play politics with – the general interest must be the only compass.”