On Wednesday, September 17th, the monochrome-rainbow fictions of the Great Airborne Thrust for Freedom will once again be celebrated in the Dutch town of Arnhem. Prayers will be recited, bugles blown, flags lowered and falsehoods uttered, as the triumph of myth over fact is once again honoured. And at what better place than near the northern edge of the Roman Empire and its once-great colony of Xanten, which is also the home of Siegfried, begetter of an entire pantheon of mythologies? Other myths have since taken root in nearby Nijmegen, replacing any factual history in the minds of most people who “know” anything about this part of Netherlands Rhine-land.

One great myth – meaning here a widely-believed falsehood – is that the huge airborne operation to defeat Nazi Germany eighty-one years ago this month could have been successful, and only bad luck and poor generalship by the British robbed the Allied airborne operation of victory. At almost every level, this is untrue. There was no possibility whatever of the Allies winning. None. It did not exist. What did exist was the passionate belief within the Allied leadership that a single bold blow could end the war within five months of the Normandy invasion.

Perhaps it is only the dementia that accompanied the Covid “pandemic” of 2020 which gives us today an almost unique sense of the power of a common delusion that can derange an entire governing class. As in 2020, so also in 1944, with here a plan, agreed by all responsible Western allied generals, to send a single thrust of armour one hundred kilometres into the Ruhr valley, then to conquer Nazi Germany’s industrial heartland and end the war.

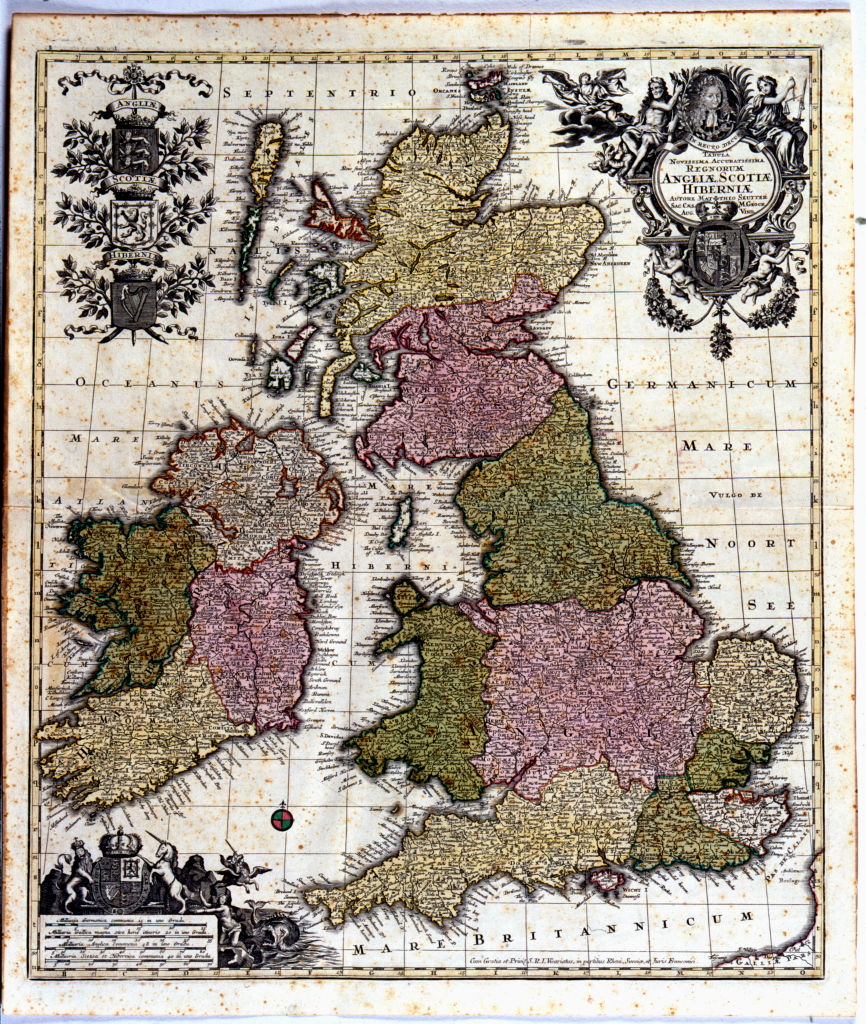

Incomplete intelligence was also a primary begetter of the Arnhem disaster. The insights of Ultra/Enigma machines at Bletchley Park left many areas of ignorance that intense war-fighting had created. One of these was that vast numbers of German troops were escaping from the murderous cauldron of Normandy into the Netherlands, a country with perhaps the most naturally perfect defensive-possibilities in all of Europe: Myriads of water-courses, with embanked single-track roads along which any invader – now meaning the Allies – must take their armour, alongside woodlands and orchards. With evil innocence, these could conceal German troops armed with “panzerfausts”, namely German bazookas. With a single rocket worth perhaps the price of a car-tyre, a single paratrooper could paralyse an entire armoured column. The path to both hell and Arnhem was paved with good intentions.

Myths need heroes. Julian Cook – played by (who else?) Robert Redford in the film, A Bridge Too Far – was a perfect hero in the gallant improvised crossing of the Rhine in frail canoes by paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division. That the crossing was indeed heroic is indisputable, but the conclusion that the men of the 82nd were then betrayed by the British who refused to proceed to Arnhem is totally wrong. This fiction is usually enhanced by images of the British nonchalantly drinking tea rather than driving on to rescue their fellow-countrymen of the First Airborne.

Mythically inconvenient truth: At this time of year so close to the equinox, sunset came at 6.50pm. The 82nd completed their crossing at 7pm. Only a madman would take armour along an embanked single-track road in the the dark alongside the orchards and dykes that festoon Rhine-land’s shores. Moreover, any such advance could only occur once ammunition and fuel had been shuttled up to the point of the allied spear, the Irish Guards. But how could this happen, when the entire length of the lance was, completely against expectations, under attack from zealous German paratroopers and SS fanatics? So, yes, this entire project was insane: But had it not accepted by all Allied commanders, from Eisenhower downwards? There are many hands scribbling the death certificates for thousands of gallant soldiers here, but most of them were innocent of malignant intentions. Was it not better to end the war in 1944 rather than endure another winter of Nazi genocide?

September 17 this year will no doubt see yet further anthems to the indomitable courage of the First British Airborne Division: However, this was not quite as doughty as official myth proclaims. One indicator of a unit’s fighting morale is the willingness of private soldiers to fight independently of their officers’ goadings, measured in the ratio of officer/private soldiers’ deaths. The Irish Guards, for example, had a ratio of three soldiers killed for every officer killed, whereas the much vaunted Paras had a ratio of rather less than 2 to 1. The South Staffordshires of First Airborne at Arnhem had a dismal parity: One private soldier for every officer. Not exactly indomitable, but thoroughly human nonetheless.

“Thoroughly human” is of course not the stuff of myths, a coinage in which Churchill was a master-minter. Of the calamity that had just befallen the British First Airborne and its virtual destruction, his initial (and private) reaction to an appalled Field Marshal Smuts ran: “I think you have got Arnhem a little out of focus. The battle was a decided victory, but the leading division (was) asking, quite rightly, for the chop. I have not sustained any feeling of disappointment over this, and am glad our commanders are capable of running these kinds of risks. I like the situation on the western front….”

In the Commons, however, his eye now resolutely on future wartime myth, he intoned sonorously of the calamity that had engulfed First Airborne that had gone in with 9,000 men and come out with 2,000, “’Not in vain’ is the boast of those who returned…’Not in vain’ is the boast of those who fell.”

Actually, “in vain” quite accurately sums up Arnhem’s outcome. However, no words can convey the catastrophe that befell the people of the Netherlands in the months that followed, as the Nazis punished them ruthlessly for their heroic support for the Allied incursion along those impossible polders, their deadly dykes and the endless waterways. Tens of thousands of Dutch people were studiously starved to death or casually murdered for the crime of being patriots. This is of course remembered in the Netherlands, but barely whispered by those whose resonant rhetoric annually recalls the gallantry of American, British, Irish and Polish soldiery eighty-one years ago this month.

Meanwhile, the Rhine waters amble on towards their ancient appointment with the North Sea, renewing old friendships while wisely ignoring the mythic ephemera from their oddly-peopled shores. Did these strangely uncouth folk not once similarly talk of Romulus and Apollo? Jesus and Mary? Siegfried and Luther? Yet still they babble. Do they never learn?

Kevin Myers is an Irish journalist, author and broadcaster. He has reported on the wars in Northern Ireland, where he worked throughout the 1970s, Beirut and Bosnia.

Nothing simple or cheap about the ‘friction, energy and violence’ of wind power