When state-owned entities are endowed with privileges that shield them from competition and allow them to ignore the realities of the market, Governments create effective coercive monopolies that can do great harm.

Bulgargaz and Bulgartransgaz, part of the state-owned Bulgarian Energy Holdings (BEH), provide a case study of that reality. Bulgargaz has a record of obstructing competition, inflicting economic damage and acting as if the objectives of EU energy policies and the legislation that underpin them do not apply to it. Its malign impacts are not confined to Bulgaria.

The dominance that Bulgargaz wields in Bulgaria’s energy sector comes at a significant cost. A 2013 report by the EU Commission commented on the “high energy intensity, low energy efficiency, and deficient environmental infrastructure” that exists in Bulgaria. Eleven years after that report, and 17 years after joining the EU, Bulgaria uses four times more energy per unit of GDP than the EU average and Bulgarian citizens are denied the benefits of an integrated and competitive single European energy market.

While the member states that entered the EU from 2004 onwards have cut their carbon intensity, Bulgaria barely shifted the dial on its figures. In the energy sector, the coercive control exercised by Bulgargaz leaves Bulgaria out of step with EU partners and out of line with the EU’s green transition objectives.

In December 2018 the EU Commission hit BEH and its subsidiaries Bulgargaz and Bulgartransgaz with a €77 million fine for blocking competitors’ access to key infrastructure and breaching EU antitrust rules. The decision followed a years-long investigation by the Commission.

Rather than enter into meaningful discussions as to what could be done to bring Bulgaria into compliance with EU rules the Bulgarian response to the investigation was combative.

The Bulgarian Energy Minister made it clear that the administration had no intention of opening Bulgaria’s gas infrastructure. The very idea was seen as threatening Bulgaria’s national security. Prime Minister Borisov labelled any privatisation in the gas sector be a “betrayal.”

In October 2023 the General Court said that while Bulgargaz had a dominant position as an exclusive user of the gas infrastructure the Commission had failed to prove that this had caused difficulties for the third parties when they requested access. While a setback for the Commission the Court’s finding is open to appeal.

In 2019 the Bulgarian government made what was seen as a positive response to the BEH case when it introduced a Gas Release Programme (GRP) that would make significant amounts of gas available to third parties “spurring the liberalisation of the Bulgarian gas market”.

The programme which was due to become operational in January 2023 was axed in December 2022.

Responding to Parliamentary questions on the matter the EU Commission explained that as GRP was based on “voluntary national legislation”. It could not act against the decision to drop it. Commissioner Simson added however that it “will not hesitate to intervene if it were to identify breaches of EU energy rules or commercial conduct on the part of BEH that could infringe the EU competition rules”.

The extent to which the interests of Bulgargaz override all other considerations was dramatically demonstrated in Bulgaria’s response to EU measures introduced following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In June 2022 EU Gas Storage Regulations were introduced to meet the challenges posed by the war. The Regulations required that underground gas storage in Member States’ territories be filled to at least 80% capacity before the winter of 2022/2023 and 90% thereafter. To protect the enterprises that helped to meet the gas storage requirements Member States were required to “take all necessary measures including providing financial incentives or compensation to market participants”.

In breach of every EU norm, Bulgargaz was the sole beneficiary of the financial measures introduced by Bulgaria. Private operators who contributed to Bulgaria’s gas storage programme have been left out in the cold, forced to carry the substantial burden of financing the gas that was purchased when world prices for natural gas were at an all-time high from their own resources.

While the measures introduced by Bulgaria fall short of the June 2022 requirements, the EU Commission has been slow to act.

The most dramatic demonstration of the belief that seems to exist within Bulgaria’s energy bureaucracy that it has a right to make up the rules as it goes along is to be found in the extraordinary agreement that Bulgargaz signed with its Turkish state-owned counterpart BOTAS on January 3 2023.

Signed just three months before Bulgaria’s fifth general election in two years, the agreement provides that the entire capacity at the key interconnection point between the Bulgarian and the Turkish gas transmission networks will be exclusively reserved for BOTAS and Bulgargaz. This strengthens the stranglehold on competition enjoyed by Bulgargaz over private operators in Bulgaria.

The agreement gives Bulgargaz the capacity to import 1.85 billion cubic metres of gas through the interconnection point. That privilege comes with a hefty price tag. Bulgargaz must pay BOTAS an annual service fee of € 2 billion. The fee must be paid whether Bulgargaz uses its full capacity or not. As the agreement runs for thirteen years, it puts a potentially eye-watering financial burden on Bulgargaz and by extension on Bulgaria.

BOTAS will pay Bulgargaz an annual fee of €138 million for the access it gains through the Bulgarian pipelines. For that payment, BOTAS also gets the right to sell gas to customers in Bulgarian customers, an odd concession given Bulgargaz’s antipathy to homegrown competition In the Bulgarian market.

It provides Russia with a backdoor through which rebranded Russian gas can enter the EU networks frustrating EU efforts to control Russian gas exports into Europe. A requirement in the agreement which deals with the origin of the gas coming through the infrastructure is confidential.

The agreement also has relevance in Russia’s war with Ukraine. A surprising amount of Russian gas travels through pipelines that cross Ukraine. The Centre on Global Energy Policy estimates that 35-40 million cubic metres per day are shipped through Ukrainian pipelines daily.

Ukraine has little option but to allow Russian gas to transit over its territory. It derives significant transit fees from the process, income that it can ill afford to lose. Ukraine also remains dependent on Russian gas. The agreement which covers the use of Ukrainian pipelines for Russian gas runs to the end of 2024. While renewal has always looked unlikely the BOTAS – Bulgargaz agreement makes ending the agreement less problematic for Russia.

Another political downside of the agreement is that it gives Turkish political leadership a significant lever for use in future dealings with the EU. This amounts to an additional erosion of EU energy sovereignty.

The BOTAS – Bulgargaz agreement could prove to be a red line crossed for Bulgargaz.

Within Bulgaria where the company has enjoyed extraordinary political cover and an extraordinary level of impunity the Botas agreement may herald a turning point.

Members of the Bulgarian government which took office in June 2023 have attacked the agreement. Prime Minister Nikolay Denkov called it “non-transparent and unprofitable”. Energy Minister Rumen Radev labelled it as potentially costing Bulgaria “billions without resulting in any benefit”. The Denkov government has launched a general review of the policies of the previous administration including an examination of the BOTAS – Bulgargaz deal.

The EU Commission has also launched a probe into the agreement. How long that investigation will take and the level of cooperation that it will receive is a matter of speculation.

There have been other signs that patience is running out in Brussels. The Commission’s 2018 fine on BEH was a first indicator. While the Commission did not act when Bulgaria dropped the Gas Release Programme, Commissioner Simson responded to a question in the EU Parliament that the Commission was exchanging information with Bulgaria “to understand the impact of the decision”. Earlier this month the Commission issued a formal notice to Bulgaria regarding its failure to comply with the requirements of the Gas Supply Regulation, indicating that if reporting requirements in the Regulation remain unfulfilled it would issue a Reasoned Opinion.

Bulgaria’s high energy intensity and other problems referred to in the Commission’s 2013 report are part of the price of the coercive monopoly that dominates Bulgaria’s energy sector. The dangers that arise from the BOTAS-Bulgargaz agreement are a reminder that the problems with Bulgargaz do not stop at Bulgaria’s border.

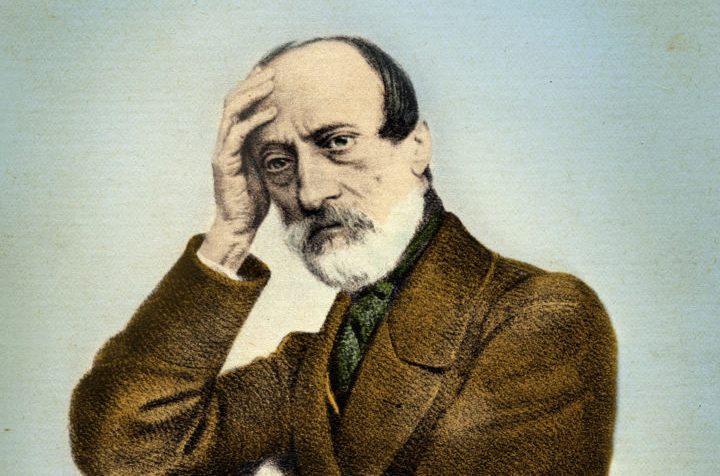

Dick Roche is a former Irish Minister for EU Affairs and former Minister for the Environment

Ireland’s ex-Europe Minister: The Bulgaria-Turkey gas deal is wrong for Europe – it creates a back route for Russian sanctions busting