While I agree with the premise that Donald Trump’s return to the presidency will be a good thing for the United States, I am a little less sanguine about what is going to happen in Europe. The European leadership in Brussels, but also in the dominant capitals, Berlin and Paris, has a tendency towards severe cases of cognitive dissonance: No matter how strongly the people reject their policies, the decision is always to double down on them.

Take, for example, the issue of migration. Almost nothing bothers Europeans (and Americans) more than the loss of cultural and social cohesion they are experiencing in their daily lives, with economic issues being mostly a secondary concern. Trump, when he came down the escalator in 2015 to announce his run for the presidency, realised this and built his entire movement around the question of migration. In the fall of 2024, it finally paid off: He was re-elected and just a few days ago returned triumphantly to the White House.

And he did not lose any time fulfilling his promises. For example, executive orders say refugees admitted to the US must have a significant probability of integrating into American society. This approach, prioritising national cohesion over unchecked altruism, presents a contentious yet pragmatic stance on immigration policy. Clearly, Trump wants to put the interests of the American state and people first and is giving up “pathological altruism” that has afflicted much of the West. Similarly, illegal border crossings at the Southern border will be stopped, and being born in America to parents who are non-citizens and are in the country on a visa or vacation will not automatically grant US citizenship.

Now compare this to the European Union: “On 04/10/2024, in a landmark decision, the Court of Justice of the European Union, Third Chamber, ruled that cumulative discriminatory measures against Afghan women under the Taliban, such as restrictions on education, employment, healthcare, and freedom of movement, qualify as acts of persecution under Directive 2011/95/EU. The decision underscores that Afghan women, as a group, face inherent risks, making them eligible for refugee status without needing an individual assessment based on personal circumstances.”

In other words, if you happen to be a woman from Afghanistan, you are immediately granted refugee status under EU law. With the stroke of a pen, the “Court of Justice” has decided that 19 million Afghan women would have the right to claim asylum in Europe. While the US is reducing the number of people that can claim asylum, the European Union is expanding it. The hubris of a court that thinks it can decide the constitutive parts of a sovereign nation’s population based on some form of universal human right is – as far as I know – without historic precedent. There are many places in the world where minorities and especially women face inherent risks, including Sudan, Somalia, and almost all of Sub-Saharan Africa. The “Court of Justice” more or less issued an invitation to half the population of the developing world, detaching the question of asylum from the matter of national sovereignty and reducing it to a matter of logistics: If you make it to Europe, you can stay. Not because the elected government in the state you arrive in says so, but because an unelected court in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg did.

So no matter for whom the people of Europe cast their vote, an entrenched bureaucracy can simply ignore it. You want to limit migration? Tough luck; a collection of judges in a foreign country has decided that you, Hans German or Pierre France, no longer have a say in the matter. Say whatever you want about Donald Trump, at least he was elected and he can be held accountable by the people. In Europe, who can hold the “Court of Justice” accountable?

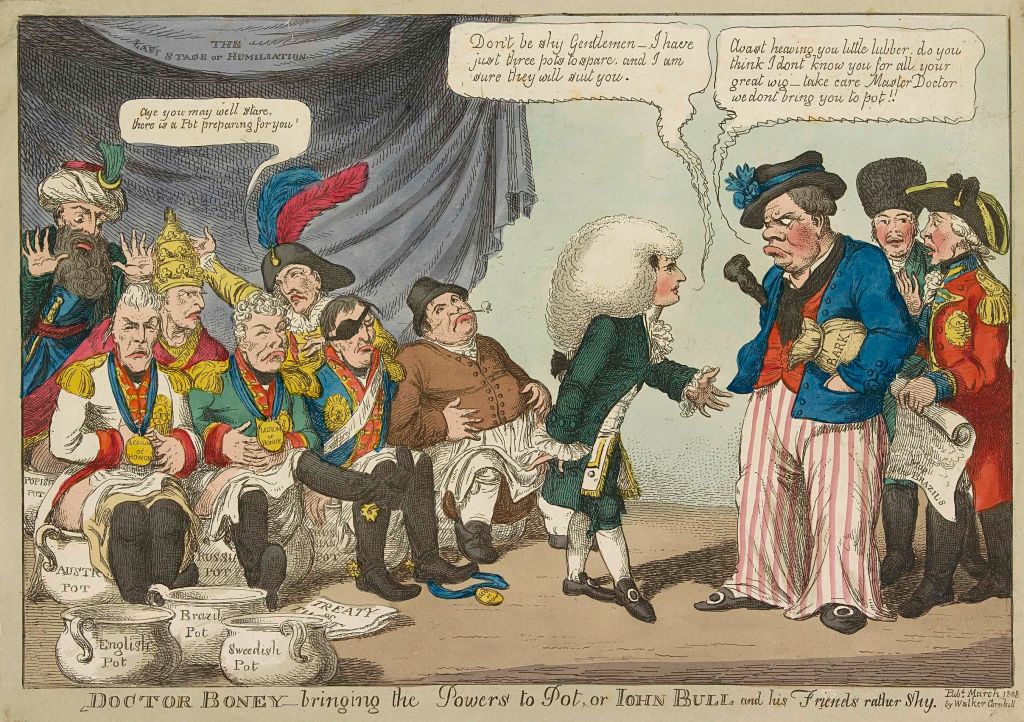

The problem with the EU is not just the politicians in charge, but also the institutional culture that permeates the entire European project. The supranational vision the EU has been built on has reached its limits, and transferring more and more power from national capitals to Brussels will not change this fact. Neither will the increasingly imperial attitude of the Brussels bureaucracy that thinks it can replace the voluntary surrendering of power to the EU with a forced one. When former EU Commissioner Thierry Breton insinuates that elections in Germany could be annulled if the Alternative for Germany (AfD) should get too many votes, he is not speaking as the representative of a union, but as a wannabe colonial enforcer, for whom the will of the German people is just a nuisance at the periphery of his empire.

Yet Breton is not a cause, but a symptom of the problem. He expresses what the most ardent supporters of the European Union have always believed: That it is a vast bureaucratic straitjacket meant to protect the peoples of Europe from themselves, ideally by gradually and benevolently disenfranchising them. A thick web of laws, regulations, recommendations, and legal rulings is designed to accomplish the kind of democratic tyranny that de Tocqueville described as follows: “Society will develop a new kind of servitude which covers the surface of society with a network of complicated rules, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate. It does not tyrannize but compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies a people, till each nation is reduced to nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd.”

This is the nutshell version of what the current cadre of European politicians is dreaming of: a world devoid of original minds and energetic characters where everyone is a sheep and they are the shepherds. They do not hate Elon Musk because he is a Nazi or a “threat to democracy”. They hate him because he is an energetic and original mind.

And, by the way, so is Trump – and quite a handful of Europe’s so-called “far right.” For all their flaws, they want to do things differently, while the status-quo elite still sticks to former Chancellor Merkel’s idea of Alternativlosigkeit (there are no alternatives). As the US election has shown, however, there are alternatives, and that is something we should all embrace. Only a system that can change and adapt can survive, while those who fail to do so will wither away.

I usually find comparisons between the EU and the USSR a bit overwrought, but in this respect, they are appropriate: Like Moscow before, Brussels lacks the ability to correct course in a changing environment, doubling down on failing policies instead. The United States has demonstrated that a course correction is possible. Can the same be said of Europe? At the moment, I fear the answer to this question is no.

Imperialism not a replacement for good governance, it is its consequence