Costly investments in the now-bankrupt Swedish “green” battery manufacturer Northvolt have drawn mounting criticism, with accusations that some pension funds may have broken the law to funnel money into the company.

On April 14, the parliamentary Finance Committee decided it would question the funds’ CEOs next month, regarding the accusations and the processes by which the funding was granted.

In an interview aired by Swedish national broadcaster SVT on April 8, Katarina Staaf, CEO of the Sixth Swedish National Pension Fund, revealed that she had chosen not to invest in Northvolt, calling it “too risky”.

“Entering a large company, which is in an early phase and without profitability, is outside our strategy,” Staaf explained.

Her statement raised eyebrows, given that her fund — which is legally allowed to invest in unlisted companies — was considered by many as the most suitable of all Swedish pension funds to make such a high-risk investment on behalf of savers.

Unlisted companies including Northvolt could potentially deliver large returns, particularly if they grew into successful businesses, although the risks were higher.

These companies typically offered limited transparency and their valuations were much harder to assess than those of publicly traded firms.

“It requires quite a lot of expertise to do this type of business and a lot of analytical capacity,” noted Per Bolund, former Green Party minister for financial markets until 2021.

Despite their legal limitations, other Swedish pension funds — which are generally barred from investing in high-risk ventures — collectively poured 5.8 billion Swedish krona (€528 million) into Northvolt. That investment has now been lost following the company’s collapse.

Some funds were suspected of bypassing Swedish law by being routed through a joint investment company, possibly in violation of their legal mandate.

The investments have come under scrutiny, raising broader questions about oversight, risk management and the protection of pension savers’ assets.

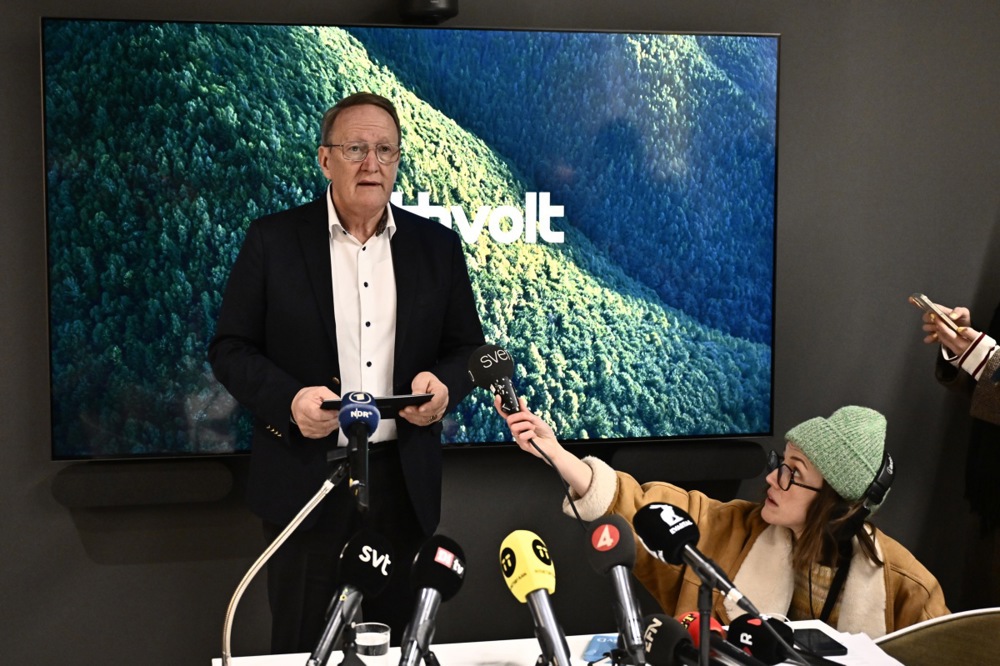

Current Minister for Financial Markets Niklas Wykman said he wanted more answers from the pension funds’ executives who had invested, in particular about the company arrangement they used to be able to buy shares in Northvolt.

“I expect those responsible for the pension funds to step forward and account for their decisions and their activities,” Wykman told SVT.

SVT said it has been trying for several months to secure interviews with the CEOs about the Northvolt investment, but they all refused.

“It is a natural part of the job for the [pension funds] to tell and explain what they are doing,” Wykman said.

The pension funds always argued that the investment aligned with their mandate to support sustainable, long-term growth, given Northvolt’s promise to bolster Europe’s green transition.

Critics countered that the funds ignored red flags, such as Northvolt’s unproven scalability and production delays, prioritising political and environmental optics over financial prudence.

SVT revealed a few days ago that the funds were invested in Northvolt through an arrangement involving a recently acquired warehouse company. This company was registered under the name 4 to 1 Investments AB.

It was alleged that this method was used to bypass the ban on buying shares directly in companies that were not listed on the stock exchange.

For now, it remained unclear if laws were broken, but Wykman said he did not rule out “tightening or changes in this legislation”.

A few years back, the law was amended, allowing pension funds to make co-investments in unlisted companies through unlisted venture capital firms — if they did not assume operational management responsibility in these venture capital companies.

This meant they could not select individual companies for equity investments.

Despite that, research by SVT showed that the pension funds’ venture capital company was a structure without employees.

“Documents at the Swedish Companies Registration Office, among others, show that the [pension funds] bought a warehouse company less than two months before the first share purchase in Northvolt, as well as a limited partnership,” the broadcaster said.

“When the purchase of Northvolt shares was announced on 9 June, even the [pension funds’] chosen name for the limited partnership, 4 to 1 Investments, had yet to be registered with the Swedish Companies Registration Office.

“Thus, the opportunities for the [pension funds’] venture capital companies to analyse and decide on the Northvolt deal appear to have been very small,” STV said.

In addition, it said, the pension funds appointed their own officials to the board of directors of the venture capital company.

In response to the allegations, Sweden’s big four pension funds issued a joint statement on April 11 insisting they had “transparently and extensively answered questions from SVT and other media”, contradicting the claims from the journalists.

They added that they “welcome the opportunity to inform the Finance Committee on 6 May and contribute with further clarity to the issues raised in the media reporting”.

“The [pension funds’] investment in 4 to 1 Investments and thereby Northvolt was made in line with the AP Funds Act and its investment rules, which state that unlisted shares may be owned through a venture capital company,” the funds said in their statement.

“In order to strengthen 4 to 1 Investments’ internal capacity, external expertise was taken on with responsibility for the ongoing management, as well as to provide expertise in financial accounting and legal matters,” they added.

“We would naturally have wished that the investment in Northvolt had developed differently”.

So-called green energy has seen rapid growth across Europe, spurred by ideological and geopolitical motivations.

Despite that, more than one company has hit snags and, to some, it has increasingly appeared that many green incentive structures in the European Union were unfit for purpose.

Without lavish state subsidies, many in the green sectors have been struggling. Private investors have been pulling away from offshore energy as the industry has struggled in recent years with rising costs, supply chain bottlenecks, higher interest rates and regulatory changes.

Perhaps the most notable failure was the bankruptcy of Northvolt, once the darling of the EU elites, heralded as the answer to burgeoning Chinese battery makers.

Northvolt was able to secure billions of euros of taxpayers money in Sweden and the rest of Europe and, within seven years of its formation, had transformed from a modest start-up into a key player in Europe’s green energy transition.

From a team of 50 employees in 2017, it grew to 5,860 staff by 2023 — a feat that would have been unattainable without substantial capital injections.

Rather than being an independent green innovator, Northvolt uses old Chinese technology, with 20-year-old equipment that was already out of date when put in place. https://t.co/oCI3Guhuj5

— Brussels Signal (@brusselssignal) October 9, 2024

Much backing came from institutions such as the EU Innovation Fund and the European Investment Bank (EIB).

At the start of 2024, the EIB injected nearly €1 billion into Northvolt’s gigafactory in northern Sweden.

In late November, an EIB spokesperson confirmed to Brussels Signal that €313 million remained outstanding, guaranteed under the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI).

Securing EU funding was usually notoriously complex, particularly for smaller companies navigating the bloc’s intricate application processes. Northvolt, though, appeared to have had an exceptional ability to unlock substantial sums.

InnoEnergy, an EU-supported investment entity, also facilitated Northvolt’s growth and received shares in the company.

Amid Northvolt’s financial challenges in autumn 2024, when it was clear it was in deep trouble, InnoEnergy was among the few entities to publicly commit additional backing.

InnoEnergy CEO Diego Pavia emphasised the importance of investor loyalty, stating at the time: “We’re helping the party – significantly.”

Secret contracts between the European Commission and “green” NGOs were reportedly part of an alleged “shadow lobbying scheme”, according to a Dutch newspaper. https://t.co/cAWxagk9TA

— Brussels Signal (@brusselssignal) January 23, 2025