Belgium has put an end to unlimited unemployment benefit.

It was the last country where jobseekers could continue receiving support for life, a system that long puzzled its neighbours and divided opinion at home.

The government has, though, now moved to close off lifetime payments and bring its system in line with its neighbours.

Today, unemployed Belgians started receiving letters announcing the end of their benefits from the national employment office.

The chief economist at Belgian Bank KBC , Hans Dewachter, told Brussels Signal today the reform “will certainly tighten the system and push the unemployed to remain or become employable”.

But he cautioned that the underlying problem was not just joblessness but also the broader “long-term drop-out from the labour market, including [for] sickness”.

For him, the challenge was structural. “The employment rate in Belgium is significantly lower than our peers. This has to do with weak activation but also with the mismatch between supply and demand,” he said.

Arne Maes, senior economist at BNP Paribas Fortis, also urged caution. Speaking September 15, he said: “The exact impact of our unemployment system compared with that abroad is not so easy to express in figures. It is therefore very doubtful whether the announced measures will have a major impact.”

At the same time, he stressed that Belgium ranked among the world leaders for labour productivity. “It seems very unlikely that raising our [low] employment rate would not come at the expense of this average labour productivity,” he said.

Official figures showed in August that Belgium was an outlier. According to Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union, 43.3 per cent of unemployed Belgians were long-term unemployed in 2023.

France was at 26.4 per cent, Spain at 34.4 per cent, Germany at 30.9 per cent and the Netherlands 13.5 per cent.

In the EU, only Italy with 54.8 per cent, Greece with 49 per cent, Bulgaria on 61.9 per cent and Slovakia at 65.1 per cent recorded worse figures.

Stijn Baert, professor of labour economics at the Belgian University of Ghent told Brussels Signal that only Croatia, Romania, Greece and Italy do worse than Belgium in term of number of unemployed who are not looking for a job.

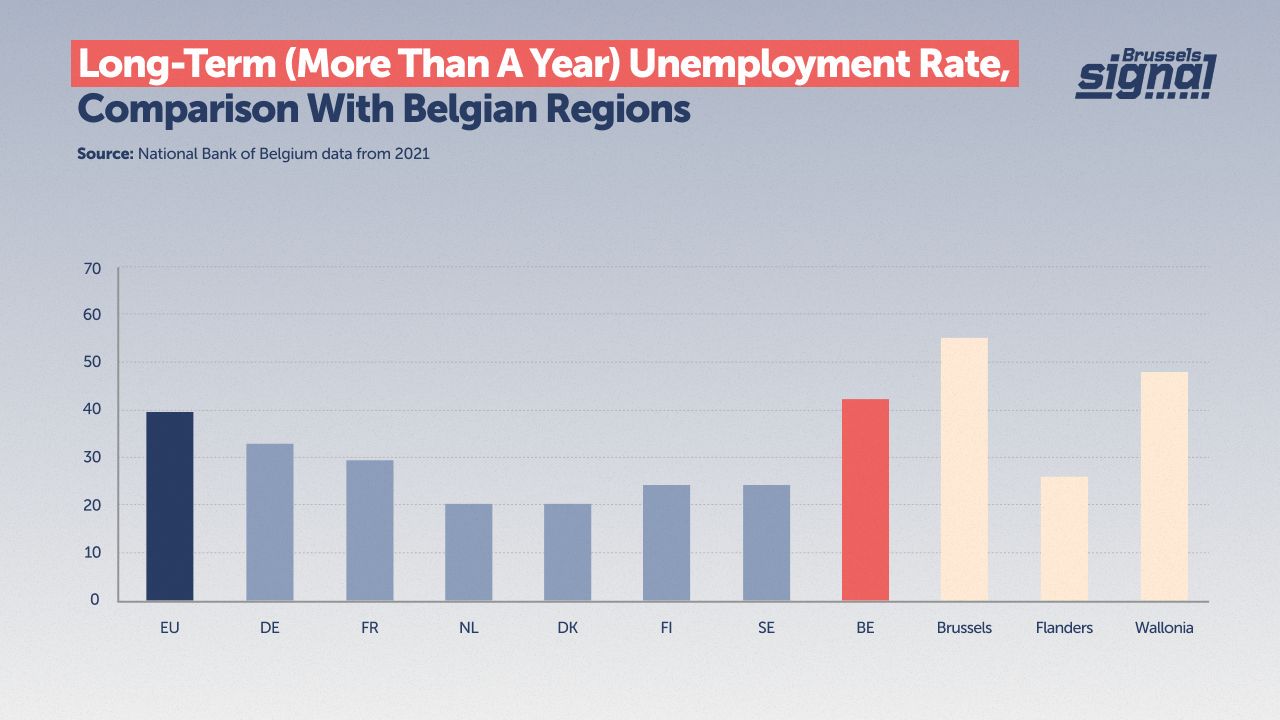

National Bank of Belgium (NBB) numbers told a similar story for 2021, where 42.3 per cent of jobseekers in Belgium had been unemployed for more than a year, compared with an EU average of 39.5 per cent.

The contrast inside the country is striking: Brussels clocks 55.1 per cent and Wallonia 48.4 per cent, while Flanders was at 26.3 per cent, one of the few regions performing close to France at 29 per cent.

In northern Europe the figures were lower — Sweden and Finland both came in at around 24 per cent and Denmark was close to 20 per cent.

Baert said international research showed that some unemployed people would move into jobs when their benefits ended.

“There is a certain moral hazard in this benefit,” he told Brussels Signal today.

Yet, he warned, the reform risks driving more people into inactivity. “Of all our 25- to 64-year-olds, 75.5 per cent are in work. 3.7 per cent are unemployed, which is a normal figure in Europe.

“But 20.9 per cent are inactive. That is 1.3 million people who neither work nor look for work”, Baert said.

He added that waiting two years before benefits are cut comes too long “because people are already locked in to non-employment, with psychosocial barriers, no new experience, and stigma from employers.”

“Of course it is absurd that despite all the vacancies in this country people can still reach the two-year mark. But you should intervene in the first six months — not after”.

Employers often viewed the long-term unemployed as lacking motivation or skills and were difficult to train.

Baert argued for a sharper decline in benefits instead. “It would be much more important to make them degressive — higher at the start, then decreasing faster.”

Unions indicated they were alarmed. The General Labour Federation of Belgium (ABVV) stressed that unemployment benefits were not a privilege but a safety net. Even if payments were cut, people did not simply disappear from the system: Many fell back on lower-level social assistance.

“The safety net does not disappear, but it becomes thinner,” the ABVV stated. For the body, the risk is that the reform deepens poverty without raising employment.

The government insists otherwise. It frames the change as part of its “summer package” of reforms, which also overhaul labour market rules more broadly.

Ministers argue that in a country with a low employment rate and a high proportion of inactive citizens, there was no alternative but to force people back to work sooner.

Elsewhere in Europe, France restricts benefits to around two years, Germany applies similar limits, and the Netherlands cuts support after a maximum of 24 months.