What is a “pole“? I believe in the ongoing debate about uni- and multipolarity we have to establish what the characteristics of a pole are, independently of their number. When we talk about a pole in geopolitics, it describes a geographical region that is dominated by a single state that has the ability to influence or dominate the behaviour of other states in that region. In other words, multipolarity is just a euphemism for a world divided into different regions that are controlled by a local hegemon that tries to establish a sphere of interest.

The popular claim that the end of the unipolar order and the so-called rules-based liberal international order will be replaced by both a new era of sovereignty as well as multipolarity has a massive internal contradiction: There will be no new universal sovereignty, only the sovereignty of regional hegemons who most likely will be more aggressive than the US has been as the sole, unipolar hegemon. Criticizing the US has been fashionable for both the intelligentsia on the Left and the Right, but in hindsight Washington was enacting mostly a hands-off approach during its unipolar moment.

In fact, until 2001 and the beginning of the mismanaged global war on terror, the decade of the 1990s only saw US interventions with significant international support, as happened after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait or the Balkan wars. Other than that, the United States allowed most countries to chart their own course relatively independently, and often played a supporting role. China’s rise was buoyed by almost all US Presidents until Donald Trump, culminating in China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in December 2001. Even Russia, supposedly the mortal enemy of the US, was not constantly humiliated or put in its place, as Moscow apologists would have us believe. Moscow was deepening its economic relations with Europe to the point where the latter became entirely dependent in the realm of energy, while George W. Bush was cooing how he “looked the man [Putin] in the eye. I found him to be very straightforward and trustworthy.” Barack Obama mocked his Republican rival during the 2012 presidential campaign, retorting to Mitt Romney’s comment that Russia is a geopolitical rival: “The 80s called and they want their foreign policy back.”

Then there are some like Jeffrey Sachs who claim Europe is under US occupation or becoming a vassal of Washington, as the European Council on Foreign Relations recently wrote. Sure, there are significant contingents of American troops in Europe, and it is also true that often Europe had to pay a price for US foreign policy blunders, like the mass migration triggered by ill-advised interventions in the Middle East. That being said, however, nobody forced the Europeans to outsource entirely their security and foreign policy to the US (and their energy needs to Russia). These were self-inflicted blunders rivalling those committed by the US, and they do not change the fact that the benevolent American hegemony over Europe allowed the Old Continent to become one of the most prosperous regions on the planet. If being a US vassal means lavish welfare systems including five weeks paid vacation and 13 to 14 months yearly salaries (like in “occupied” Germany) and no money for defence, since that bill is picked up by the US taxpayer, I wonder why anyone would not want to sign up for vassalage?

That everyone from Brussels to Berlin slept through the digital revolution and decided that subsidizing an unsustainable welfare state is more important than to create an ecosystem for innovation and production was not the result of some evil scheming by the Americans, but idiocy by Europeans who still believe you can replace entrepreneurs with regulators and fossil fuels (and nuclear) with wind turbines and solar panels that have to be imported from China.

The “luxury of idiocy” will no longer be affordable in a multipolar world, especially as the US will scale down their engagement in Europe. If you thought US mingling in European affairs was bad, wait until you see how it is going to be without it. Although it might seem counterintuitive, a unipolar world with one strong hegemon would allow for more national sovereignty than a multipolar world with numerous regional hegemons. Because in such a world, the regional hegemons need to extract more from their imperial periphery in order to remain competitive – or so many of them will think.

Donald Trump, in his usual intuitive fashion, has realized where the world is headed: “Trump is ‘100 per cent serious’ about acquiring Greenland and the Panama Canal”, say sources close to the president-elect. I do not think that Mr. Trump is reading my column, but his open call for neo-imperialism comes a week after I published my first article on the issue, so there might be something to it.

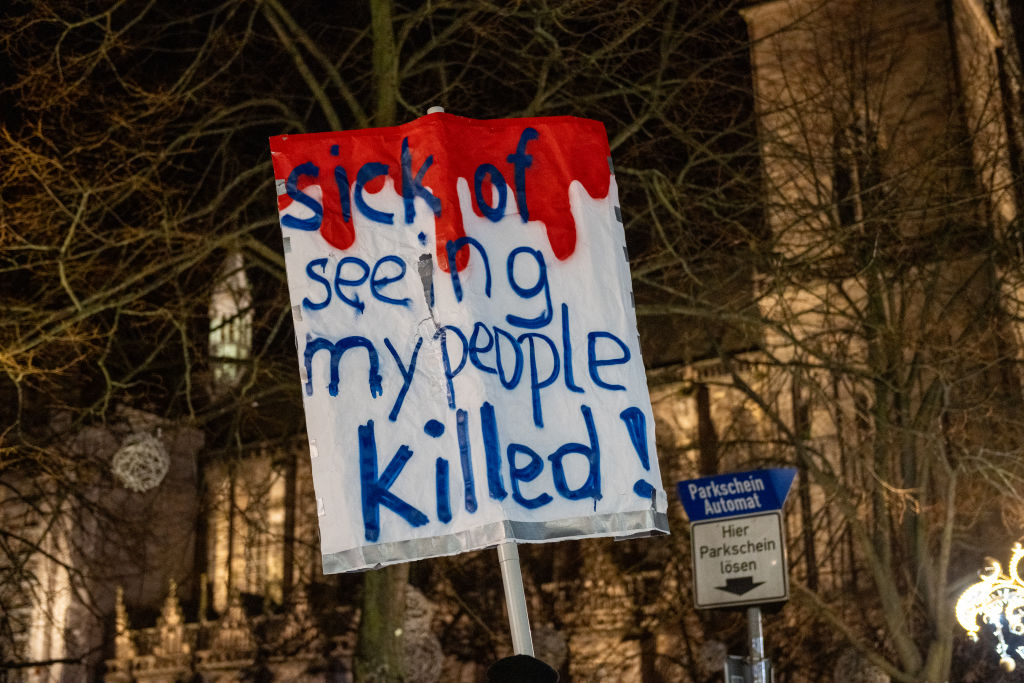

That he is also referring to Canada as the 51st State with Justin Trudeau as the “governor” is just the usual Trumpian hyperbole, but it does reflect a deeper issue: In a world that is divided into spheres of interest (or poles, if you prefer), the core states will try to position themselves as geopolitically advantageous as possible – and if this should mean an end to Ukrainian, Taiwanese, or Greenland’s authority over their own affairs, so be it. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was not only driven by a sense of humiliation or some deep-seated sense of unity with the Ukrainian people (before killing them in the thousands) but because it has strategic importance as a transit country to Europe and as a crucial puzzle piece for controlling the Black Sea. For this reason, you also see ever more Russian meddling everywhere from Georgia to Romania. The multipolar world is like a giant chessboard, and Russia just happened to make the opening move.

In a similar vein, China’s interest in reunification with Taiwan is not just of an ideological nature, but also driven by geopolitical calculations. Taiwan is a key element of the so-called “first island chain,” the chain of islands encompassing Japan, Taiwan, portions of the Philippines, and Indonesia, separating the East and South China Seas from the wider Pacific. This “chain” is where US and Chinese perceived spheres of influence overlap, and both regional hegemons will exert considerable pressure on the island nations caught up in the middle. Tensions between China and the Philippines have already increased significantly, and there is no reason to think that under heightened US-Chinese competition these tensions will abate.

From the increased sanctions imposed on Chinese technology companies to initiatives aimed at redirecting global capital from Chinese markets to US assets, the situation is evolving rapidly. Currently, the United States holds approximately 85 per cent of the world’s financial assets, a level of dominance that has granted the Treasury considerable influence over China and other countries attempting to oppose the Western financial framework. While the US exercises its economic strength, China has been diligently striving to counteract these efforts. In recent years, Beijing has intensified its efforts to reduce reliance on Western-centric global financial systems, focusing on creating alternative trade routes and financial infrastructures—such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—to lessen the effects of US-imposed sanctions. Beijing has also begun to retaliate by imposing export bans on crucial raw materials like gallium, germanium and antimony which are critical for military equipment and the high-tech industry. This in turn will most likely force the US to find alternative sources, and “persuade” them to deliver, meaning more neo-imperial pressure on the horizon.

In this changing geopolitical environment, it will become increasingly difficult to be a mere bystander, so more and more countries will attempt to get into the game: Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia, and other will have to decide whether they should try to become the regional hegemon or subjugate to one. None of this makes a stable and peaceful world more likely. In this gathering storm, the question remains what Europe should do, and how it could best position itself. Some ideas on this will be forthcoming in the third part of this essay.

Is it time for Neo-Imperialism?